Class Independence, socialism, and electoral politics

Tom Roud writes on the prospect of party politics for socialists in New Zealand, and how to relate to electoral politics. First published in May 2023 for volume three of The Commonweal.

Election year is once again upon us, and the usual debates and discussions begin to be steadily and inexorably ground through the discourse mill. These can range from the inane to the asinine, with some far too rare moments of relief in the form of genuine insight. Whether you’re a loyal supporter of a major (or minor) party, through to an anarchist decrying the foolishness of voting at all (‘it only encourages them!’), there is a feeling of inevitability in both the debates about, and the outcome of, the election: ‘Whoever wins, we lose’.

It may be an insurmountable task, but I intend to write something that is of the more interesting variety – somewhere between a musing and a proposal. This will require some context, meaning the common discussion points and their origins.

Left and Right – two sides of the new Party of Order

The political designations of ‘left wing’ and ‘right wing’ have their origins in the French Revolution. In 1789 members of the National Assembly sat themselves either to right or the left of the president based on whether they supported the revolution (left) or the King (right). From this we get the idea of the ‘party of movement’, committed to progress, change, liberalisation, and the ‘party of order’, with a conservative commitment to maintaining the status quo.

Since these early days it is fair to say that representative democracy, elections, and the legitimacy of specific political regimes have changed and developed considerably. Suffrage itself has expanded in the West to almost all citizens of a liberal democracy, with prisoners being a notable exception in many states. So too the terms of engagement have shifted significantly. Few in the mainstream right -wing party in this country would have a particular loyalty to hereditary monarchy. Nonetheless, the dynamic of ‘movement’ versus ‘conservation’ holds.

Growing out of the Socialist movement of the early 20th century, the New Zealand Labour Party is quite a good representation of the ‘party of movement’. Significant reforms in this country tend to be spearheaded by Labour, rather than their National Party adversaries.

The more well-known (and palatable to their loyalists) examples of this are the First Labour Government who, from 1935 to 1949, effectively established what became known as the post-war compromise: a form of liberal democracy and capitalist economy that sought to curb the worst excesses of a free market with state intervention in the economy and public investment. Prior to this, governments tended not to burden themselves overmuch with the ravages of poverty, often leaving churches and civil organisations to aid the worst off, and they generally let the market operate as it saw fit. There were some counterexamples, Pember-Reeves and Seddon in the Liberal tradition here, or Bismark’s Staatssozialismus (state socialism) reforms in the late 19th century. While the United-Reform Coalition (later National Party) had begun to shift some of its economic thinking as the Great Depression deepened, it was Labour’s electoral victory in 1935 that set the course for the country for much of the rest of that century. While National would still govern more often than Labour, the basics were established and largely left in place for some time.

As oil shocks and other economic pressures started to impact New Zealand in the 1970s, Labour once again proved its worth as the ‘party of movement’. This time, however, the fourth Labour Government elected in 1984 determined that state bureaucracy, intervention in the market, and investment to alleviate the suffering of the worst-off in society was precisely the problem to be solved. With an extraordinary programme now known well as ‘neoliberalism’, the Labour Party reorganised the country in ways all of us are still living with.

In both cases, Labour has set the beat and National have then solidified and deepened the changes. Through this steady, cyclical process our own major parties of movement and order have negotiated the twentieth century and beyond.

But does this analysis really hold? As a simplistic description of the dance between two major parties it is near enough for our purposes. With over a century of this process behind us, though, we would do better to see this dance as order itself. The appearance of opposition, competition, difference without any content of significance. Let us take either party and ask: given carte blanche to enact their political and economic programme where does power sit? It stays precisely where it has always been, with the state – its laws, courts, politicians, and with capital – with the individuals and boards, shareholders and lobbyists, captains of industry and diffuse trusts, and banks. Order is maintained now not through the conservative tendency of one party, but through the left/right/left/right/hoof beat of both. Perhaps a hoof is not the best imagery, as even a pack horse has some spirit too – that thumping is instead the metallic thud of the machine.

The alternatives?

Now we get to the well-trod arguments of what to do instead. If these two major parties are moribund, lacking any character beyond that of the machinations of capital, what are we to do? Let’s quickly look at some of the answers.

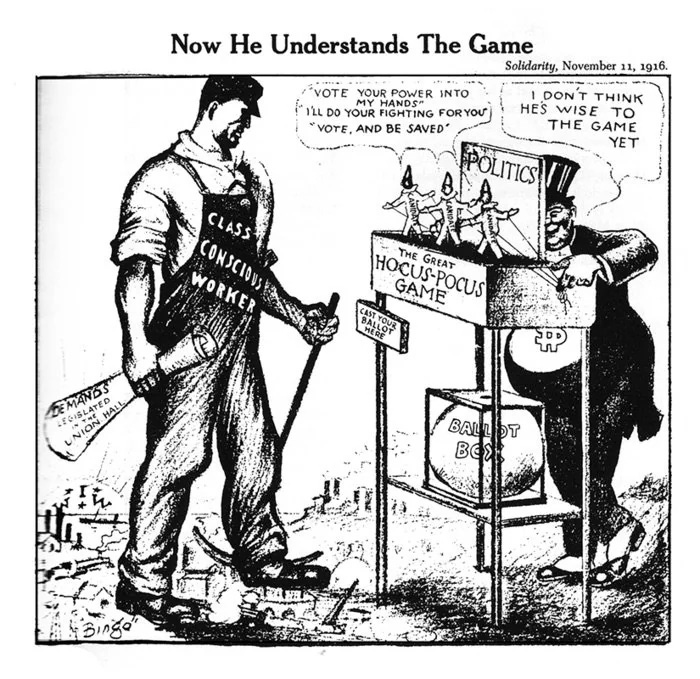

My anarchist friends have had an answer for a very long time now: don’t vote, absolute abstention from the electoral process as fundamentally moribund. Of course, that is not their whole answer. There is power in community, in the streets, in organising directly in the workplace to exercise power where a worker has it most. A fine enough answer – what partisan of the workers movement who believes that the working class must take power would really oppose any of these things? Moreover, it does have the appearance of some class independence – we do not accept the legitimacy of elections and as such abstain from them. The trouble is there is indeed power in the streets (the police), in the community (landlords), and in the workplace (employment law and the threat of punishment should you breach them). Anarchism does not remove itself from social reality, and aspects of social reality are determined by the outcome of elections whether one participates in them or not. To put it another way, the anarchist answer is to refuse the question.

Vote for the Greens? On the spectrum of left-to-right most would accept the Greens as ‘more left’ than Labour, and they’re certainly more strident with questions of social progressivism. They appear more interested in change, both faster and more significant. Some of them even used to be anarchists, apparently. In an MMP environment a vote for the Greens does, to the extent that this is a meaningful metric, result in a ‘more left’ government – or a more left opposition. What it does not do, and seemingly never will, is provide an alternative to the machine. Consider the 2020 election. For the first time, and perhaps the only time it is likely to happen, the Labour Party could govern alone. The Greens, that party of terribly radical former activists with CVs well adorned with identity markers – proving their individuality and truly representative nature – chose not to be across the benches to hold one wing of the party of order to account. It is unlikely they’ll ever have the opportunity to do so with such low stakes again (the Labour Government still would have been in power, so they wouldn’t even be smeared as ‘wreckers’). As such, their independence is skin deep only. Whether or not what they champion is working class politics (and I do not believe it is), they are currently an appendage of Labour. They will assist Labour with making whatever change seems necessary to leave power precisely where it is, and National will eventually win an election and consolidate this new state of affairs – same as the old state of affairs, with a human face.

We are thinking about this all wrong

Perhaps the title for this subsection is unfair. After all, I am writing it. I am, as Alan Moore has put it, using words to conjure thoughts and images in your head – casting a spell, in a sense. Perhaps you were thinking about this much more clearly and it is my writing that has brought you down this cul-de-sac.

Let us recalibrate. Perhaps the question of who to vote for, or whether to vote at all, is basically immaterial. If the machine operates as I have described here, it is unlikely that the impact of voting (or not, for that matter) is very important. I’m sorry to say that if you are looking for an answer about who to vote for, or whether to bother at all, you won’t find it here.

Socialists, as I understand it, aim to establish a state of affairs where working people come to power at all levels of society and set about reorganising it. This is not an immediately attainable goal, which can be deeply frustrating, but it calls on socialists to force themselves to think much more long term than an electoral cycle. So while I am not imploring you to vote (or not), I think it would be mistaken to present a socialist answer to the electoral question this year with the options in front of us. Do as you please in October, now we can turn to the real question.

Party, Programme, Independence, and Opposition

I understand many socialists may be satisfied with the call to focus our energy elsewhere, to ignore elections, to effectively agree with the anarchists whether we are Marxists or socialists of some other stripe entirely. My assessment of electoral politics as the theatrical form that allows for the machine to continue unabated is not, however, an injunction to not give a shit about any of this. To quote a friend, in an article that was sadly never published (regardless of its inflammatory style):

This is, unfortunately, the House of Parliament - where ugly and infinitely vulgar MPs’s fat arses are arraigned for hours on end, in disgusting and antiquated rituals of formal ‘debate’. But all the same, their debates become Law. The capitalist class is not uninterested in the power of this institution. In fact it invests enormous amounts into it through its parties and members. ‘How embarrassing!’ says the anti-Parliamentary socialist of today. ‘For the real power resides in ad hoc and ideologically confused anti-fascist rallies at the steps of Parliament […] that climax in a nice political speech against racism from the Greens!’

So now we delve into a great heresy, one that may leave me hammering this article to the doors of a cathedral all alone. I do not reject the parliamentary road to power. In fact, I believe precisely what is needed for our movement is an independent party with a programme - one neither limp and conciliatory, nor utopian and impossibilist - that can intervene at the level of high politics while continuing to contribute to the enormous amount of work required to build working class power at every other level society.

Party - we all know what this means, or perhaps not, but in the oldest usage the word ‘party’ was not even offensive to the anarchists. A collective of people working towards a similar political goal - in a sense we already have something like this in the Federation, if much too small to be influential, and perhaps with goals too vaguely defined. Nevertheless, to be disinterested in what is referred to as ‘high politics’ and retreat purely to the workplace and community ignores, as I’ve alluded to earlier, the way that the exercise of power through high politics influences the workplace and the community.

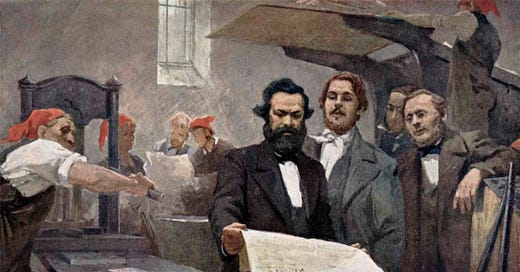

Programme - A party is an empty vessel without one, and there are many to draw from. The Communist Manifesto of 1848 was, in a way, a programme for a party that didn’t exist. Contrarily, The Erfurt Programme of 1891 was the articulation of a very large and serious party, and it’s elaboration in Kautsky’s The Class Struggle (1892) laid the basis for what would become orthodox Marxism for some decades. Influential in many small (though declining) sects now, Trotsky’s Transitional Programme of 1938, or Bordiga’s Lyon’s Theses (1926), all take it as necessary for any political organisation of the working class to have some specifically articulated goals.

The content of each of these programmes vary greatly. If you talk to some of the more paranoid citizens of our society they often note how many planks of the Communist Manifesto have been enacted by our own governments. Marx and Engels themselves admitted not long after its publication that the platform articulated in the manifesto was out of date. Kautsky’s intervention, enormously aided and informed by Engels, sought to influence the Second International - made up of socialist parties from many nations and encompassing millions of members and supporters in total. Bordiga, an interesting Italian Marxist somewhat lost to history in the English speaking world, was one of the few to call Stalin the gravedigger of the revolution to his face. Sometimes described as ‘more Leninist than Lenin’, Amadeo Bordiga helped write the Terms of Membership to the Communist International, and his Lyon’s Theses were in part an attempt to clarify and rearticulate a genuine Marxist position in the face of ComIntern Stalinisation. Bordiga was so committed to the programme as central to any Marxist organisation that he’d be quite disgusted at my willingness to write about him as an individual at all. The transitional programme, to some degree or another, has basically been absorbed into revolutionary socialist assumptions for decades now - our friends in Socialist Aotearoa, the International Socialist Organisation, Fightback, Redline, and the International Bolshevik Tendency all owe a great deal of their consideration of programme and political activity to this 1938 document.

While the content of these programmes vary greatly, what they have in common is important: they are of their time. The context in which they are written, the purpose of their articulation at all, is enormously influential.

Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.

This quote from Marx is very popular, but the emphasis placed upon aspects of it has been misleading. In the socialist left today, for example, it is assumed that ‘transmitted from the past’ is so important that any new programme must build upon the previous programmes of our history. Considering the near total disintegration of Marxist politics in the West this seems so optimistic as to veer into delusion. Instead the emphasis must be made that what we do is not in circumstances under which we would prefer - and today, in New Zealand, that may mean confronting the very real possibility that a revolutionary programme, inherited from Marx via Trotsky or whomever else is entirely inappropriate to our conditions.

What, then, are our conditions? We exist in a country that is small in population though not particularly small in landmass. We are geographically isolated, and while generalised globalisation of production has reduced the impact of ‘time’ on the flows of capital, it is apparent that in any significant crisis we may be overlooked as an insignificant market not worth catering to as far as supply chain magnates are concerned ;consider, for example, the number of container ships that delayed visiting New Zealand for great lengths of time during the Covid-19 pandemic. Working class people in this country are disempowered on multiple levels - not only do we lack significant ability to determine the state of affairs at our workplaces, the fact that New Zealand never truly industrialised and was instead kept as a farm for the British motherland means that, in the contemporary world economy, we have retreated into a collection of economic cul-de-sacs which we seem unable to escape. This country runs on; 1) primary industry which owes very little to ‘value added’ by labour, preferring to export raw or near-raw products, 2) the ‘FIRE’ (Finance, Insurance, Real Estate) economy as detailed by Jane Kelsey - an industry that is excellent at extracting profit without ever increasing the total amount of useful goods on the planet, and 3) service work - whether that be in tourism or more localised. None of these industries provide the opportunity for workers within them to exercise their power particularly well. This does not mean that small scale industrial activity is impossible, or not beneficial. It does mean, however, that should any mass movement of the working class seek to take the reins of production under their own control and redirect them towards pro-human (rather than pro-capital) ends, they would find themselves directing smoke and mirrors - we would not want for dairy or unprocessed pine logs, I suppose.

With this in mind, my thinking on the question of a political programme for a socialist (or similar) party to take would have to consider a serious reorganisation of the national economy. While socialism ‘in one country’ is untenable for both geopolitical and resource related reasons, the ability to have some aspects of economic sovereignty with which to build a new way of doing things is paramount - to begin a process while we wait for other geographic regions to take similar steps. The post-colonial experience of Africa and elsewhere is a testament to this fact, as there is no way to build any sort of society when your economy is dependent upon an international system that would prefer that you fail. As such, while the democratisation and elevation of workers power throughout the economy would be similar to a great deal of socialist programmes, I believe the immediate task of a pro working class programme in this country would be more Wolfgang Rosenberg than Rosa Luxemburg. It is not that we need to re-shore industry in order to have workers in positions of power within the economy, more that we need to establish some of these industries at all in a country which has been somewhat shielded from ever having to do so due to political and economic relationships with our colonial betters. This will take significant state direction which no party today has the forethought or inclination to consider.

Radical phrases and demands may be cathartic, but they do not really contest power. A mass democratic party, armed with a programme that seeks to suppress the needs of the market in the interest of working-class power - even if that programme seems quite moderate to many of those currently on the far left - will be rightly treated as a significantly more of a threat than any sloganeering.

Independence - For a party to be independent it needs to be largely self -reliant. Learning from the best periods of our history is informative here. In the late 19th and early 20th century, Social Democratic Parties (as they were called at the time) were not merely electoral vehicles but were instead social and civic organisations of a scale hard to imagine today. The SPD in Germany, for whom Kautsky elucidated the programme I mentioned earlier, had under its auspices an enormous variety of social clubs, sports teams, vocational organisations, and so on. While recreating this in its entirety is unlikely, due to the changes in the capitalist state since this time, ordinary civil society, while largely depoliticised, is happy enough to fill in many gaps for working class people which used to be ignored - there is no need for a workers’ party to organise workers’ sports teams for example when access to these has become much easier, nor is leisure a case of ‘do it yourself’ as capitalism finds it quite lucrative to sell entertainment even to the working class. Nevertheless, there are still many ways in which ordinary working people are not served by the current system in questions of community, connection, education, and conviviality. As austerity knocks at our door, and economic downturn appears likely, the atrophying of what remains of civil society will no doubt accelerate. By being well positioned to intervene in these periods of decay and provide independent forms of social organisation, a party may have a dynamic and deeply rooted life of its own which will in turn facilitate an independence from the ‘good graces’ of those already in power. While social reality is often codified and reflected by the state and the law, it is not over-determined by it. With an ecosystem of workers organisations any party or labour movement worth a damn would be able to weather the possibility of being made ‘illegal’ at worst, persona non grata at least, without collapsing entirely by being embedded in and improving the lives of working people.

Opposition - Perhaps the hardest sell of all of this is the notion of opposition. Socialists of any stripe - be they reformist or revolutionary, anarchist or otherwise, understand that we are deeply opposed to the way things are now. We do not imagine we can inherit all aspects of this society and simply transform them to serve pro-social, human ends. They have been created and developed over centuries to serve the interests of capital and bureaucracy, and any intervention to undo this trend will be met with extraordinarily fierce resistance by the forces of order. Moreover, partial victories and piecemeal attempts to move the dial in the direction of workers power are unlikely to be lasting, or worse, will be integrated into a new bureaucratic and capitalistic set of societal norms. As such, any party which wishes to have something resembling class independence in the electoral sphere will have to understand itself as a part of extreme opposition until such time that conditions are appropriate and the ability to enact a programme of significant’ perhaps even ‘revolutionary’, changes is possible. In the old, orthodox parlance these were considered the factors necessary for enacting a Minimum Programme. What this would mean for successful electoral candidates, or a party which has representation at the highest levels of government, is a topic for further discussion and may not be identical at local or national levels. Nonetheless, this does necessitate educating supporters and members of any such project towards a deep and long- term way of thinking about our political project.

The state as it currently exists is characterised by inertia in the form of consent-building media, as well as civil servant bureaucrats who are tasked with maintaining the status quo and handing a great deal of real power to technocrats. This is inertia in the sense of uniform motion, rather than being absolutely frozen in place - the liberal, ostensibly democratic state tends towards consistency. The ability of a radically democratic, working- class movement to actually replace these instruments of class rule will need significant organisation long before a party wins an election. Furthermore, any context under which a class party may be in a position to make serious gains would likely be in conditions of general de-legitimisation of the existing order.

I have seen sentiments of this sort described as revolutionary patience. That seems fitting advice for those of us in the Federation of Socialist Societies. Merely a few years into our project, and already numbering among the larger groups of recent decades, we would do well to continue to ‘keep our powder dry’. Let us consider what we may be able to do, and pursue an understanding of, and engagement with, social reality that may help us build the sorts of class organisation needed this century. I believe that includes an electoral party, but whatever we build should be suitable for our current situation, while having the institutional capacity to respond to changes in the balance of forces. To build an organisation designed for circumstances we are not in may as well be a socialist version of ‘The Secret’ - assuming the law of attraction will deliver us a situation in which we can live out our imagined role.

It may be that circumstances change in ways unforeseen by this document, and I don’t want to preclude the possibility that some enormous change in our society would see an argument for factionalism within the extant left. If that eventuates, I believe the principles here will still be relevant and help guide our thinking.

Vote if you want to, or not, but let’s get on with discussing what actually needs to be done.