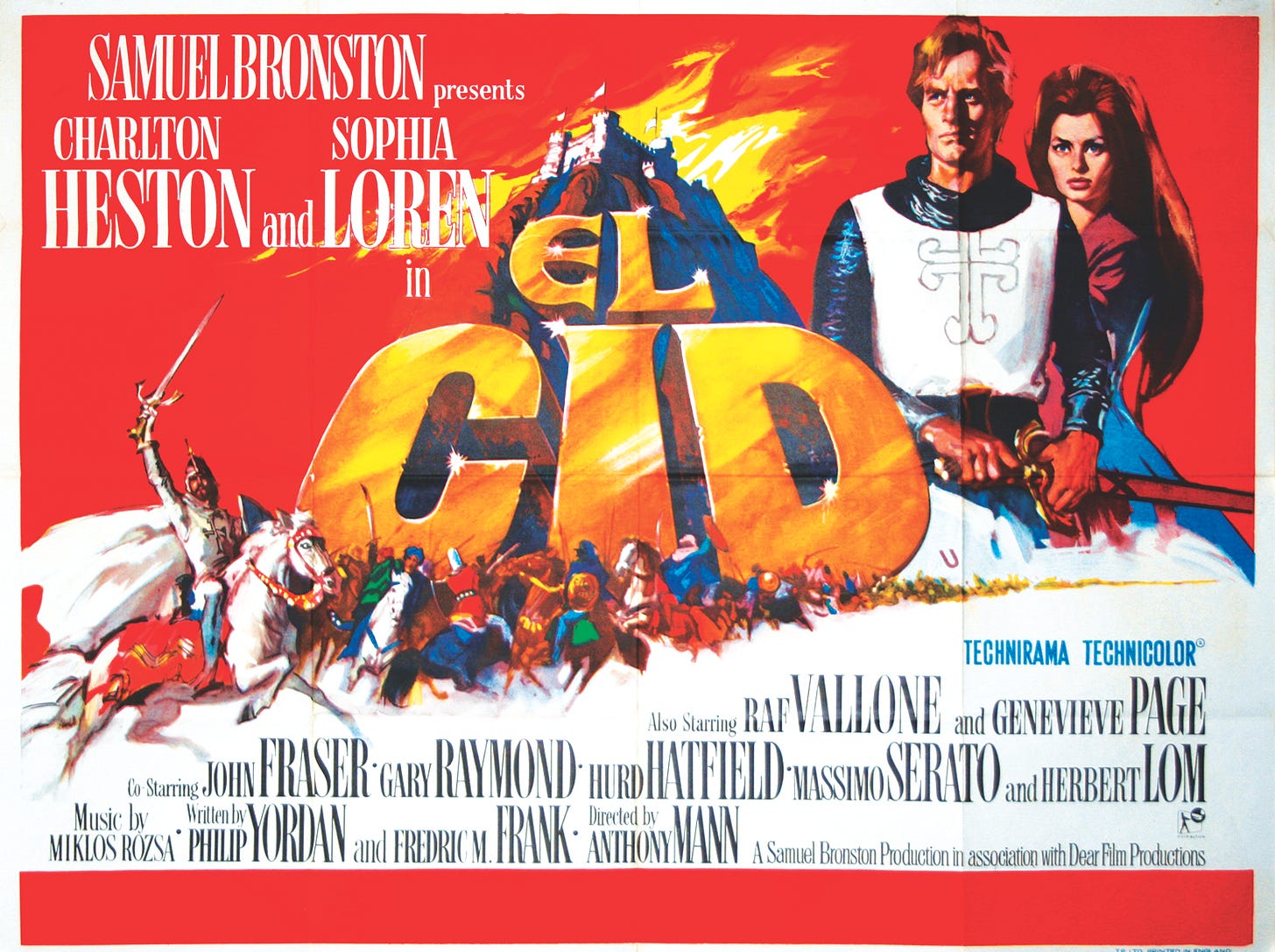

Film Review: El Cid (1961)

The blacklisted screenwriter, the Fascist dictator, Charlton Heston, and the movie they all helped make happen: Byron Clark reviews 1961 film 'El Cid'.

Fascist regimes have always relied on a kind of alternative history. Nationalism (even in its non-fascist iterations) requires storytelling. ‘Nations’ have to be constructed: through a shared language, a shared history, and often a shared folklore. Spain under the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco was no exception. ‘The image of both the Christian Reconquest and the Conquest of the Americas was dependent upon an imagining of the past that simply never was but became accepted as truth by most Spaniards,’ writes Louie Dean Valencia-García in Far-Right Revisionism and the End of History. ‘The alt-history effectively replaced history itself—and still holds a strong grip on the country’s popular imagination.’

This is perhaps most obvious in the revival of the medieval knight Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, better known as El Cid. While El Cid lived in the 11th century, long before the Reconqista and before there was a Spain (the Iberian peninsula was at that time made up of numerous Christian kingdoms and the Islamic taifas that emerged following the fracturing of the Caliphate of Córdoba), he was revived as a Spanish national hero in the 1950s. In 1955, with the support of Franco, a statue of El Cid by the artist Juan Cristóbal was erected in Burgos. Burgos is the largest town near El Cid’s birthplace, and was also a stronghold for the fascist Falange movement and Franco’s army during the Spanish Civil War. In the Francoist narrative, Spain’s Civil War was conceptualised as a ‘War of Liberation’ and framed as another ’Reconquest’. While the Reconqista expelled Muslims and Jews, the civil war had, according to Valencia-García, expelled (or otherwise ostracised, imprisoned, murdered or exiled) those from the political left, queer people and other supposed enemies of Spain.

In 1960 the Franco regime provided financial support for the production of a blockbuster film about El Cid, starring Charlton Heston. In the Francoist version of history, El Cid is an unambiguous crusader against Islam. In the film Yusuf ibn Tashufin, the Muslim antagonist to Heston’s Rodrigo, portrayed by Herbert Lom, asserts that the prophet has ordered them to rule the world and declares that to achieve that aim they will first sweep across Spain, then Europe. It’s a narrative that fits well with the far-right of the 2020s where there is a belief in a so-called ‘great replacement’ where Muslims will spread throughout Europe displacing the white, Christian population. In Franco’s time though, the reconquest of Spain and the expulsion of the Muslim Moors was likened to his own war against the forces of ‘anti-Spain’, which he identified as socialism, communism, and anti-Catholicism, a less direct historical comparison. Rather than invoking a fear of Islam in the minds of early 1960s movie goers, this line as uttered by Lom was arguably a metaphor for the domino theory of Russian expansion that was so prevalent at the time[1]

The film has been described as Francoist propaganda. In the commentary track to the 2007 DVD release, historian Neal Rosendorf stresses the Francoist themes in the film. After interviewing Charlton Heston while conducting research for his book A Knight at the Movies: Medieval History on Film, John Aberth described him as seemingly ‘blissfully unaware that he reenacted on the set of Peñiscola a Fascist leadership cult.’ When Aberth outright asked Heston if the political climate of Fascist Spain inadvertently affected the film in any way, a ‘genuinely puzzled’ Heston responded, ‘I can’t think how.’

The opening narration of the El Cid film echoes a speech made by Franco in 1936, where he stated:

We are in a war that is resembling more and more the character of a crusade, of a great historical campaign, and of a transcendental struggle of people and civilizations. This war has chosen Spain again in history, like a battlefield of tragedy and honour, to save herself and to bring peace to a world gone mad.

Was Heston ignorant of all this? Quite possibly. During the eight months he spent working on the picture in Spain his only interaction with the Spanish populace was a ‘public relations exercise’ at a bullfight in Castellón de la Plana, where he paraded with the matadors atop the same white horse he rides in the movie. Franco was never invited on set, though Prince Juan Carlos was, and met with the stars. Aberth writes that ‘the political message would have been unmistakable to a population only a generation removed from the Civil War. To them, the Cid was the Middle Ages’ Franco, a medieval justification for the current regime.’

For American audiences though, and perhaps even the American actors, what they took from the movie was equally likely a narrative around racial equality that paralleled the contemporary civil rights movement. That may be in part due to the fact that the screenplay for this medieval costume epic, derided by many as fascist propaganda, was written by a Jewish communist.

Shortly before the filming was scheduled to begin both Heston and his co-star, the Italian actress Sophia Loren, expressed dissatisfaction with the script, with Loren threatening to abandon El Cid unless it was rewritten. Ben Barzman was brought in to redo the script at short notice. Barzman was one of five blacklisted screenwriters who often worked in Madrid for producer Philip Yordon. It was not uncommon for screenwriters blacklisted in the USA to work abroad, often still writing scripts for films that were made for the American market. Barzman, according to his wife Norma, adapted the script from Pierre Corneille’s play Le Cid, which was first performed in Paris in 1636. The play contains little in the way of historically accurate material.

Ben Barzman was born in Toronto in 1911, the son of an old-time Socialist who had emigrated from Russia in 1905. He put himself through college ‘standing on my feet [for] long hours’ in a Portland cloak-and-suit factory. He moved to Hollywood and was approached to join the Communist Party while working on a musical revue called Labor Pains, a West Coast version of the Broadway musical Pins and Needles, created by (among others) Max Danish, long-time editor of Justice, the newspaper of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). The play was first performed by a cast of ILGWU members.

After the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began investigating writers in Hollywood with real or imagined links to the Communist Party the Barzmans ended up in the UK, among other expatriates now working on British film and television. When Ben was hired to rewrite El Cid, Norma was instructed to bring with them from London five kosher salami for Philip Yordon. She delivered them on their arrival and he immediately took to one of them with his letter opener. Ben Barzman, Sophia Loren and Basilio Franchina, who had been hired to translate the dialogue into Italian and then back into simple English for Loren, were ensconced in apartments on three different floors of the Torre de Madrid. A boy sat in the hall of Ben's apartment waiting for new script pages. Ben typed, and when a few pages accumulated the boy took one set to director Anthony Mann and another to Sophia. From this process the final script emerged.

Anthony Mann was no ideologue. ‘I believe in the nobility of the human spirit. It is that for which I look in a subject I am to direct....This is what drama is. This is what pictures are all about. I don't believe in anything else’, he said when describing his last epic film. But movies are always influenced by the zeitgeist, ‘We tried to make it all as modern as possible so that it could be related to any society; so that people would understand’, he said of The Fall of the Roman Empire, the epic he directed immediately after El Cid. Martin M Winkler, in an article titled Mythic and Cinematic Traditions in Anthony Mann's "El Cid"’,[2] argues this also applies to the El Cid picture:

Mann's Rodrigo is both a hero from the mythical past and a child of the modern age. He is liberal and open-minded toward people of another race and culture, and he presents such an ideal image of the progressive American that a reviewer for Time magazine did not hesitate to call him a ‘champion of civil rights.’

At one point in the film Rodrigo tells a Muslim leader ‘We have so much to give to each other, and to Spain.’ There is perhaps some truth in this characterisation. Contrary to Francoist myth Rodrigo was no crusader, but a mercenary who fought in the service of both Christian kings and Muslim emirs. The name ‘El Cid’ is derived from the Arabic honorific al-sīd (‘the lord’). Historia Roderici (‘The History of Rodrigo’), a Latin prose life of El Cid, probably written in the first quarter of the twelfth century, describes Rodrigo’s favour at the court of al-Mu’tamin of Zaragoza. The emir is described as being ‘very fond of Rodrigo’,more so even than of his own son, and as having entrusted his taifa to Rodrigo’s care. In the Historia, as in the movie, El Cid’s enemies are not the Moors of the Iberian peninsula but the Almoravids, the Muslim dynasty whose empire stretched over the western Maghreb.

Thomas Freeman, in Filming a Legend: Anthony Mann’s El Cid [3], describes the film as being simultaneously propaganda for Franco and as propaganda for racial equality, the result of the different goals of those involved in the collaborative enterprise of making an epic film.

Samuel Bronston, the producer of El Cid, wished to make a profit on the film and also to establish a major film studio based in Spain; both goals necessitated gaining Franco’s support. Other people involved in the film—the director, the scriptwriters and probably its star—wished, for ideological reasons, to depict the Cid as a champion of racial equality and racial harmony. It was possible for these two messages to co-exist within the same film because they had crucial elements in common: they both depended on portraying the Cid as an altruistic leader who united the people of Spain, both Christian and Moor, to work together in a common cause. The difference in the interpretations was whether the cause was defending Europe from Communism or the struggle for Civil Rights.

Today, nearly half a century on from the end of Franco’s regime, the town of Burgos has remained a home to far-right ideology. A group called Skinheads Burgos holds a yearly ceremony at the statue of El Cid to celebrate the expulsion of Muslims and Jews from Spain. The town also hosts a weeklong festival dedicated to El Cid. To quote Louie Dean Valencia-García again ‘the alt-history created out of the fragments of El Cid’s life is celebrated both popularly and by the radical right. With this simple example, we see just how a historical person has become twisted into something clearly unrecognisable to history.’

El Cid dies at the end of the film. His corpse is then strapped onto his horse by his wife and sent out to lead the battle in his last victory against the Almoravids. ‘It is a marvellous scene, no question’, Heston told John Aberth, ‘and it was wonderful to play. Actors love death scenes.’ Before Anthony Lom’s Yusuf ibn Tashufin is trampled and his army forced to retreat, a cheer goes up from the forces led by the dead El Cid—‘for God! The Cid! And Spain!’ The narrator then declares ‘and thus the Cid rode out of the gates of history and into legend.’ Today, as when the film was made, that legend serves as something a modern political ideology can be harnessed to, like a corpse mounted on a horse and marched into battle.

El Cid is streaming on Kanopy

[1] "The Purest Knight of All": Nation, History, and Representation in "El Cid" (1960)

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1225818

[2] Mythic and Cinematic Traditions in Anthony Mann's "El Cid"

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24780568

[3] Biography And History In Film, Thomas Freeman and David Smith, Palgrave Macmillan (2019)

Nice article but it should surely be five kosher salamis, not salami?