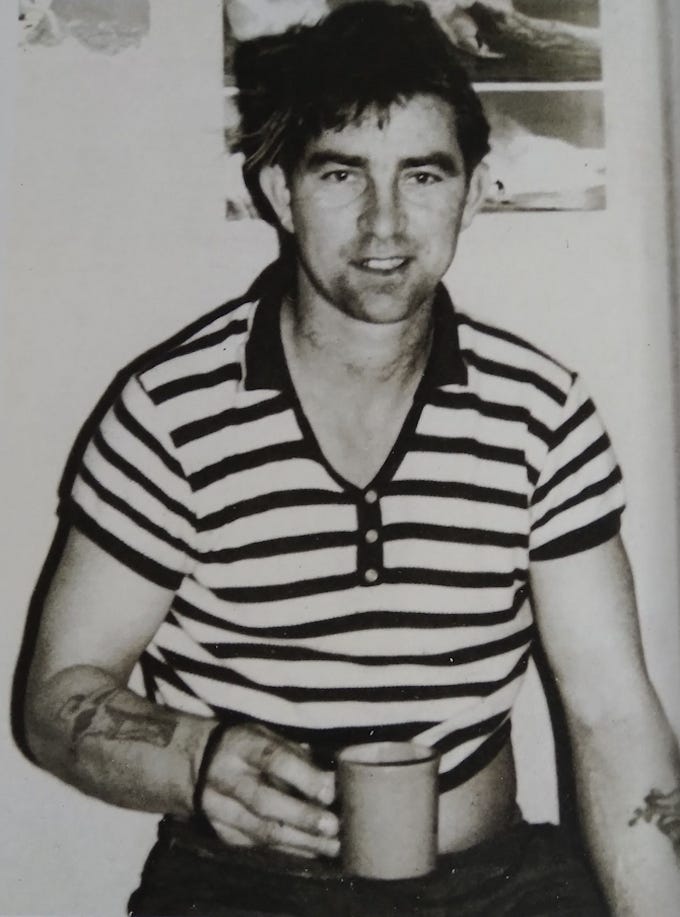

In Memory of Jimmy O’Dea (1935-2021)

David Colyer says Ave Atque Vale to veteran socialist Jimmy O'Dea. First published in October 2022 for The Commonweal, this is part one of two entries.

Last November (2021) veteran socialist Jimmy O’Dea died in Auckland at the age of 86. Jimmy was involved in some of the most well-known struggles of the past six decades. He was an early activist in the anti-nuclear and anti-apartheid movements from 1960, then in opposing the Vietnam War and supporting struggles for tino rangatiratanga on the Land March and at Bastion Point and Raglan occupations. Through the 1990s he was part of the long, and successful, state house rent strike against market rents. Underpinning all of this, he was a rank- and- file trade union activist and a vocal champion of socialism.

This tribute to Jimmy’s life is based on two interviews I recorded with Jimmy in 2009 and 2010, as well as my own memories of working with him. Jimmy was a great storyteller with an amazing memory (apologising for not remembering the name of a union delegate from 30 years earlier, only to recall it soon after).

There were many areas of his life and activism we never talked about, so these are not really covered. I’ve also left out much mention of his family – they will have their own stories to tell. The things we did discuss, his early life, and what led to him joining the Communist Party (CPNZ) are covered in some detail here in Part 1. Part 2, in the next issue of Commonweal, will focus on Jimmy’s early trade union activism, what socialism meant to him, and his role in the Bastion Point occupation.

The texts in quotation marks are Jimmy’s own, unless otherwise stated.

The terrible injustice of Ireland

Jimmy was born in Newcastle West Poor House, County Limerick. Because his mother was unmarried, he was taken by the Catholic Church. His mother managed to get him back, but then had to move where she wasn’t known. Jimmy spent his childhood in the villages of Kilmallock and Old Pallas in eastern Limerick.

It was ‘a very nationalistic area’, which is to say people had strongly supported the Irish independence movement. The history of the anti-colonial struggle was passed on in a traditional manner. If you look up Irish storytelling traditions on the internet today, you will find reference to ancient myths and legends. No doubt there was plenty of that, but Jimmy remembered learning much more recent history.’ All the old people would come on a cold winter’s night, around the fire in a big thatched house, and there’d be about ten or twelve old guys talking. They called it “tracing”, tracing history, another name for it was “cuardach.”’ Jimmy pronounced this ‘koor-deek’. An Irish dictionary translates cuardach as meaning searching, rummaging or looking for something.

‘And you’re listening there until about twelve at night, pitch dark, and you’d be listening there to all the things that happened – the Land League days, the evictions, all the things that happened in past history, up until that time’. He heard of the two attacks on the Kilmallock barracks of the Royal Irish Constabulary, first during the Fenian Rising of 1867, then when it was burned down during the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921; and of the Soloheadbeg Ambush, the first action of this war, which happened just down the road. Jimmy recalled being shown holes in the walls of houses from when the Constabulary’s Black and Tans shot up the village with machine guns.

Despite its nominal independence from the British Empire, Ireland in the 30s, 40s and 50s remained a miserable place for working class people, full of ‘terrible injustice’. The rural economy remained semi-feudal. One of Jimmy’s earliest memories, from when he was about four, was going to a hiring fair by the Kilmallock railway bridge with his mother. Here workers were hired by farmers to work for the year, but only received pay at the end of that time.

While his mother was away working, Jimmy was left in a private foster home with a dozen other children. They were often cold and hungry. One night some of the children snuck into the grounds of a mansion to scavenge bark for the fire, only to be confronted by the landowner, a Captain Lindsey. Terrified, Jimmy narked on the older girl who was hiding their axe down the front of her dress. When he was older, Jimmy learnt how to use ferrets to poach rabbits and became known for his skills as a rabbiter. As he described things in a TV interview in the 90s, ‘We were the Peasants, we were the dispossessed. Our existence came from rabbits and anything you could get.’

At the age of 19, Jimmy, like millions of other young Irish people before him, left to work overseas. Working on building sites in London, Jimmy found his anti-English prejudices challenged by the kind treatment he received from the family he boarded with, and by fellow workers who took him under their wing. One in particular warned him not to enlist in the army, pointing out the war cripples ‘who fought for freedom’ and now begged on the street.

Returning briefly to Ireland, Jimmy looked further afield. He saw an ad for assisted immigration to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The application required a certificate of ‘good character’ to be signed by a garda (police officer). The local garda chief demanded a £10 bribe (about NZ$500 today), which Jimmy refused. This dispute led to the guards attempting to beat Jimmy up, which didn’t end well for them. When I first heard this story, I wondered if it might be a case of an old man exaggerating the glories of his youth. However, corroboration came in a TVNZ program about the Irish in New Zealand. A film crew interviewed two old fellows from Jimmy’s village. They remembered the incident more or less as Jimmy described!

Looking back Jimmy considered it a lucky escape. Had he gone to Rhodesia, he joked, ‘I might have become a racist’. In the end he headed for Australia and found work in mines and railway yards. He celebrated his 21st Birthday while working on King Island, between Tasmania and the mainland. And it was there he had a conversation with another worker who had recently been in New Zealand and said the wages there were good, adding, ‘You’ve come this far, you may as well go right to the end of the world’.

A New Zealand road to socialism

Arriving in Aotearoa in 1957, Jimmy’s first job was working on the foundations of the Meremere power station, a coal-fired station in the north Waikato coal fields, 64 kilometres south of Auckland. At first he thought he was in paradise, ‘The conditions there were incredible, the food, the wages, it was all new to me… There were 40 gallon drums of orange juice and pineapple juice. There was pig, cold and hot, and chicken, you name it.’ When Jimmy praised the generosity of the employers, his union delegate Terry McCosh, a Communist originally from Liverpool, pointed out that everything on offer had been fought for by the workers. ‘He said “we’re the workers, we make all the profits” and the bosses were just giving a bit back to the workers because the union was that strong.’

Jimmy described himself at that time as ‘a naive young guy’ but said ‘I got my education at Meremere… hours and hours of discussion…’ McCosh explained ‘the history of Ireland and the history of capitalism’ and for Jimmy, who ‘was very angry, angry because of the injustice I’d seen and experienced’, the pieces fitted together like a jigsaw.

In the late 50s and early 60s the militant wing of the union movement was recovering from the defeats of the Auckland carpenters in 1949 (when the Labour government and conservative Federation of Labour leaders had stepped in to smash a Communist Party led union), and the 1951 Waterfront lockout. A booming economy and a shortage of workers made it hard for bosses to blacklist militants and more profitable to settle economic demands than fight them. As Jimmy put it, ‘It was the great years of capitalism’, and the boom allowed Communists and other militants, including those who had lost their jobs in ’51, to establish networks throughout many blue collar unions.

There were a number of Communist Party members working at Meremere and socialist literature was distributed and party meetings were held on-site. Pat Kelly, later a prominent union leader and father of former CTU president the late Helen Kelly, also joined the CPNZ around that time. Jimmy remembers him as the walking delegate (a senior union delegate still paid a wage by the boss, but who is free to spend their time on union issues). As with many big government projects, the leading contractor was an American firm. Racism from American bosses, such as calling Māori workers ‘boy’ and trying to ‘order them about’, caused one of several strikes on the job.

There was also plenty of local racism in the South Auckland and North Waikato towns at the time, many of which had segregation in hotels, movie theatres and barbershops. Jimmy mentioned the refusal of the Papakura Hotel to serve Dr Henry Bennett, a senior Psychiatrist, bringing the issue to national attention in 1959. Also brewing was the issue of Apartheid in South Africa, with Māori players being excluded from the New Zealand Rugby Union’s 1960 tour of South Africa. Working with Māori organisations and trade unionists, the Communist Party supported the ‘No Māori, No Tour’ campaign.

Other prominent CPNZ members, such as Bernie Hornfeck, later leader of the timber workers’ ‘Wildcat’ strike, and Ken Douglas, future president of the Federation of Labour and Council of Trade Unions, were drawn to the Party as a result of this campaign. Discussions I’ve had with other Party members suggest that while they often first came in contact with the Party through their union activism, it was the links the CP made between workplace struggle and issues like racism and imperialism that was the catalyst for them taking the plunge and signing up.

Jimmy himself joined the CPNZ in 1959. Around the same time he moved to Auckland, and over the next few years got married, had children and settled in a state house in Kupe Street, Ōrākei where he lived for the rest of his life.

AFTERWORD

Tracing socialist history in Aotearoa

In Jimmy O’Dea’s story we hear the voice of someone who was involved in many of the most celebrated campaigns of the past 60 years. Yet, while the anti-nuclear movement, the Maori Land March, and anti-apartheid protests are now heralded by historians and politicians alike as shaping New Zealand society for the better, the vital role of socialists and the wider labour movement in these struggles is left out.

In accounts of the history of the left (rare though these are) it is commonplace to counterpoise these ‘new social movements’ of the late 20th century with the increasingly out-dated ‘old left’ of the trade unions. But this narrative never fitted with the stories I heard from older socialists in the 90s and 2000s. As well as listening to his village elders around the fire, Jimmy gained much of his historical education through discussing with fellow workers on the job. Few of us have such opportunities today, with trade unions (let alone a socialist workers’ party) simply not existing in most workplaces.

The smashing of the union movement three decades ago created a terrible break in the continuity of our movement. Recovering something of what was destroyed is indeed a work of searching and rummaging. Twelve years ago, I started interviewing three of the oldest members of Socialist Worker, Bernie Hornfeck, Len Parker and Jimmy O’Dea, all of whom had joined the CPNZ around 1960. I wanted to record not only their memories of historic events, but to ask what socialism meant to them and what being a socialist meant for their lives. This work was cut short by the final dissolution of Socialist Worker in 2012. However, the idea of tracing the history of socialism through the words of socialist activists themselves remained and gradually broadened from a focus on one party to the entire movement.

The sheer scale of the project delayed the next steps; however over the past year, thanks to the work of a small co-ordinating committee, the NZ’s Road to Socialism Oral History Project is underway once more. Recording an oral history of the socialist movement in the second half of the 20th century remains an enormous task, and we need many more people to get involved.

Anyone interested in supporting this work can follow the NZ’s Road to Socialism page on Facebook and join the related Facebook group. Alternatively email nzroad2socialism@gmail.com

Nicely put. Looking forward to reading more of the Commonweal!

Very interesting. Connolly would have wept at how communism actually operated, and the very limited independence that, say Czechoslovakia or Hungary enjoyed. I wonder just what he would have made of the incredible prosperity of a swathe of Ireland today, the beneficiary of EU support and a turbo-capitalist business/ tax regime!