Our History: Labour Day in New Zealand

Martin Crick tracks the history of Labour Day in New Zealand. First published in October 2022 for volume two of The Commonweal.

Labour Day has been a statutory holiday in New Zealand since 1900. Originally fixed as the second Wednesday in October it was ‘Mondayised’ in 1910 and moved to the fourth Monday of that month. The origin of this holiday is closely linked to the struggles for a legal eight-hour working day.

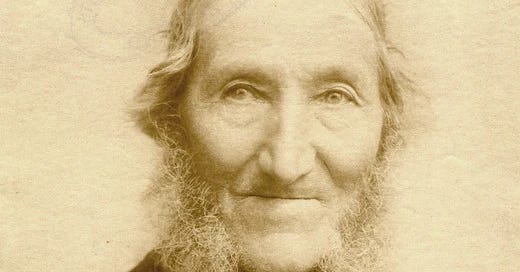

Samuel Parnell, a 29 year-old London-born carpenter, came to New Zealand in 1840, on one of the first ships to reach Wellington. He was asked by a fellow passenger, merchant George Hunter, to erect a store for him. He agreed, on condition that he worked no more than eight hours a day: ‘There are 24 hours per day given us’, he said, ‘and eight of these should be for work, eight for sleep, and the remaining eight for recreation and in which for men to do what little things they want to do for themselves.’ Although Hunter protested he had no option but to agree, due to the shortage of tradesmen. Thereafter others followed Parnell’s example, meeting incoming ships to tell new arrivals that they must insist on an eight-hour working day.

When Dunedin was settled in 1848 the men were promised an eight-hour day by the Otago Association. The following year Captain Cargill, the local agent of the New Zealand Company, tried to undermine the agreement, posting a notice that ‘according to the good old Scottish rule’ 10 hours was to be the norm. The settlers refused to accept this and he was forced to back down. Auckland building workers launched a campaign which led to the introduction of the shorter working day in 1857. But although the Handbook of New Zealand for 1875 boasted that ‘in all mechanical trades, and for labourers in general, the standard day’s work is eight hours’, this was far from the case, and many worked longer hours. Moreover, it was by custom only and was threatened whenever economic conditions deteriorated. What the trade unions wanted was a law limiting daily hours in all occupations to 8 and weekly hours to 48.

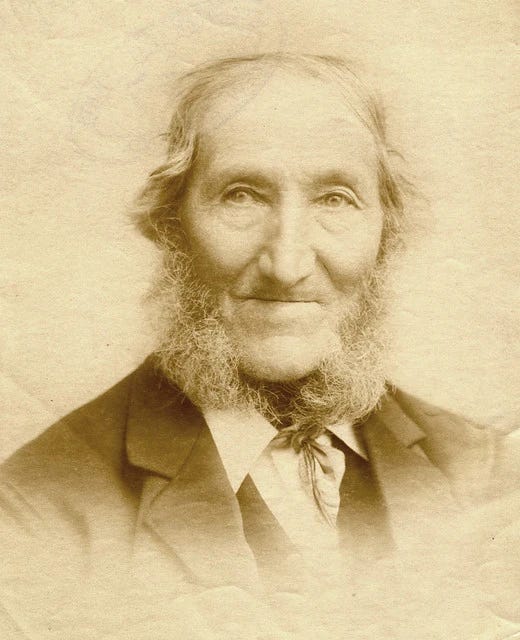

In 1882 an Auckland unionist committee decided to hold an eight-hours demonstration on Wednesday 19 April. Many building trade employers agreed to release their staff, and the demonstration set the pattern for future event:, a procession in the morning, sports and picnics in the afternoon, and a ball or concert in the evening. Otago Trades Council called a public meeting instead of a demonstration and a Dunedin MP, M.W. Green, introduced an Eight-Hour bill in parliament in May. It passed the Lower House but was defeated in the Legislative Council. Similar bills, introduced almost annually, failed for the next 20 years.

Late in 1889 seamen, watersiders, and miners joined forces in the Maritime Council. In July of that year an international labour congress in Paris had called on workers everywhere to demonstrate on 1st May 1890 for a legal eight-hour working day. Reports of the huge demonstrations in Europe and the USA clearly impacted in New Zealand and the Maritime Council, meeting on 10 May, called upon all Trades Councils to support demonstrations on 28 October, the date of the founding of the Council in 1889. Premier Harry Atkinson agreed to close all government offices for the day. However, a nationwide Maritime Strike erupted in August and its defeat led to the collapse of the Maritime Council. Nonetheless the Labour Day demonstrations were a huge success, a show of strength and a signal that labour was still a force to be reckoned with, but they were certainly not the revolutionary gatherings calling for the overthrow of the capitalist system that were witnessed in the May Day celebrations overseas. There was no socialist party or movement to lead such a call. Wellington watersiders , whose union and jobs were about to disappear, to be replaced by scab labour, carried a banner with the clasped hands symbol and the motto ‘Defence not Defiance’, and the equally doomed Lyttelton wharfies’ banner depicted a merchant and a labourer shaking hands and the inscription ‘Labour and Capital as they should be’.

Perhaps the only exception to this came in the Christchurch Labour Day parade the following year. There the Socialist Church float flew a banner with imagery drawing upon the symbolism of Walter Crane: a representation of labour at the plough, carrying Atlas and upon his shoulders the world, whereon sat triumphantly an obese capitalist. The script on the banner read ‘Labour is mocked, its just reward stolen; On its bent back sits idleness encouraged’. Inserting such sentiments into a day devoted to baby contests, bicycle races and other sporting contests didn’t sit well with the press, the Star calling it a ‘cynically primitive view of things’, and ‘a bitter doctrine of faith.’ (Christchurch Star, 10 October, 1901)

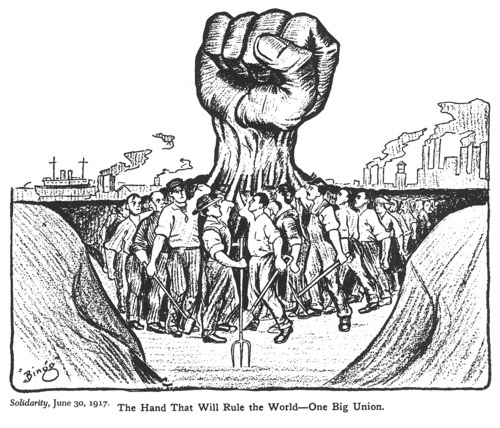

After the defeat of the Maritime strike many unskilled and semiskilled unions collapsed, and Labour Day processions became dominated by tradesmen’s societies. Increasingly too business firms entered floats in the processions, along with theatre groups and even circuses. The numbers of union marchers declined, and Christchurch and Auckland soon abandoned processions, Dunedin persisting a little longer. The afternoon sports and entertainments remained hugely popular however. In 1894 the Trades and Labour Conference agreed on the second Wednesday in October as a uniform date for the holiday and William Pember Reeves, the Minister of Labour, agreed to close government offices on that date. Once an Arbitration Court was established in 1895 many unions included an eight-hour day and a Labour Day holiday in their claims, but many still worked between 10 and 14 hours per day. Eventually, on Labour Day 1899, Parliament agreed to declare the second Wednesday in October a public holiday. Premier Seddon was well aware of calls for an independent Labour Party and wanted to ensure the Liberal hold on the unionist vote. Official recognition led to renewed enthusiasm for the processions, the one in Wellington in 1900 reported as the largest yet, but the Evening Post reported that ‘the parade is getting every year more into the hands of the enterprising businessman and out of the jurisdiction of the unionist.’ (Evening Post, 10 October 1900) Soon only Auckland of the major cities continued the traditional parades. The Industrial Unionist, journal of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW/Wobblies), commented in 1913 that ‘“Labour Day” is the bosses’ Labour Day…a street display of goods, a cheap advertising method for employers…more like an acknowledgement of subjection than an assertion of dignity’, and it urged New Zealand Workers to adopt May Day, the International Labour Day. (Industrial Unionist, 1 November 1913)

After World War 1 Auckland trade unionists made strenuous efforts to revive Labour Day parades, but after 1923 they too collapsed. The miners’ unions under communist leadership began to celebrate May Day with marches and meetings, but May Day functions received little support in the cities. One exception was a huge ‘united front’ May Day march in Christchurch in 1932. Attempts to revive Labour Day processions after Labour’s election victory in 1935 failed to gain much support and eventually even the sports and picnics faded away.

‘For about two decades after 1890’, wrote Bert Roth, ‘the annual Labour Day celebrations were a significant spectacle in New Zealand. They were an expression of class consciousness, an affirmation of the strength of the union movement and, for the tradesmen’s societies in particular, an opportunity to present the members’ skills and pride in their craft.’ However, with the coming to power of the Liberal Party after 1890, they were also an expression of class collaboration, workers parading side by side with their employers, reflecting the Lib-Lab ideology of a partnership between labour and capital. This was seen in a banner carried by Auckland bootmakers in 1891, just after their defeat in a long strike over pay and conditions. Their banner showed the traditional symbol of solidarity, a clasped handshake, but one hand issued from a rolled-up shirt sleeve, the other from a black coat-sleeve, signifying, said the Auckland Star, employer and employee as they should be. The same paper, in 1920, wrote that ‘Labour Day is a holiday to be enjoyed rather than a day of aggressive demonstration as May Day is on the continent.’