Our History: Socialist Sunday Schools

Martin Crick on the activity of Socialist Sunday Schools in early New Zealand Socialism. First published for Volume 5 of The Commonweal, May 2024.

The earliest use of secular Sunday schools by the radical movement began in Great Britain in the early 1830s amongst adherents of Robert Owen and Chartism. They operated until the 1850s and then disappeared with the decline of the early radical movement. Prior to 1870 Christian Sunday Schools provided some of the only educational opportunities for working-class children. Often associated with non-conformist churches they instructed children in the basic tenets of religion alongside basic literacy and numeracy. After the National Education Act of 1870, which introduced a system of compulsory education, often under the auspices of the Church of England, Sunday schools focused almost exclusively on instilling Christian ethics and upon moral education.

The exposure of many of the early leaders of the growing labour movement to this Sunday school system, and to the rote learning and what they saw as the indoctrination of the new national school system, led to a movement to establish secular schools to teach the values of socialism, to explain socialist ideas and labour theories in simple terms for a child audience. I suppose one could equate this with the Jesuit idea of ‘Give me a child until he is 7, and I will give you a man.’ The first Socialist Sunday School in Great Britain was established by Mary Gray, a member of the Social Democratic Federation, in Battersea, London in November 1892. Twenty years later there were approximately 120 schools throughout the country, and by 1912 over 200. A National Council of British Socialist Sunday Schools was established in 1909 and prepared a manual for the use of teachers. Publications included The Young Socialist and the Socialist Sunday School Hymn Book.

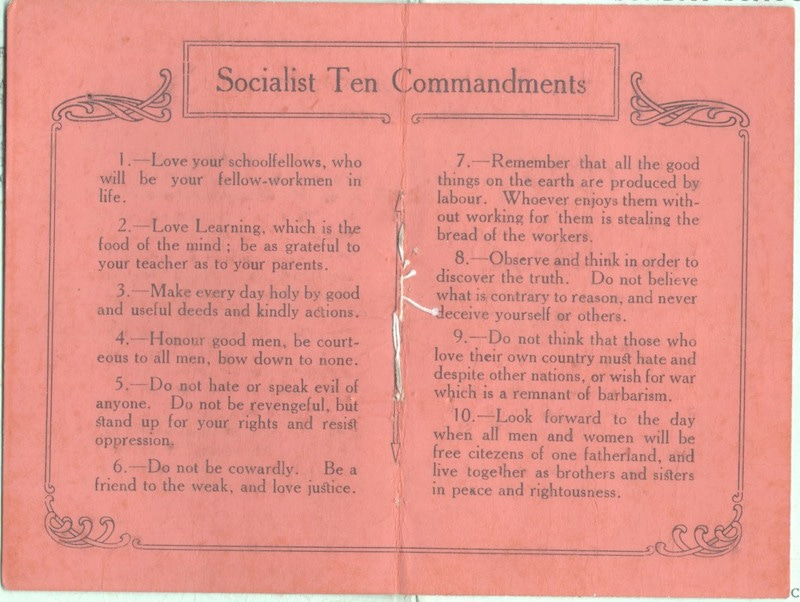

The SSS leadership maintained that public education should be secular, and the schools’ teachings were free of religious content. However, perhaps due to the religious environment of many early labour leaders, the schools made extensive use of the language of Christian ethical teachings. Thus, writing in The Young Socialist one leader of the movement, Archie McArthur, said that the aim of any young socialist should be to ‘build up the City of Love in our own hearts and so, by and by, help to build it up in the world.’ In addition to the hymn book schools also taught the Socialist Ten Commandments.

This reflected the largely ethical nature of the early British socialist movement. A typical meeting might include singing, a short lecture on an ethical or moral issue, and the recitation of an ‘Aspiration’. Schools also organised sports teams, orchestras and libraries. Parents joined too and some schools even conducted secular/socialist weddings. Inevitably they encountered opposition, being accused of blasphemy and ‘perverting the minds of the young people of the country with their political and anti-religious doctrines and teachings.’ In 1907 the London County Council evicted 5 branches from their hired school buildings and in 1927 Fulham Council refused to let the local school meet on Sundays because it was of a ‘non-theological’ character.

There was criticism on the left too, some arguing that they should focus on economic theory rather than moral development. After the First World War the newly- formed Communist Party of Great Britain rejected the schools. Increasing attacks on their quasi-religious nature, and the onset of the Great Depression further weakened the movement, and although some schools struggled on into the 1960s it eventually faded away.

The Socialist Sunday Schools had an impact upon many leading figures in the labour movement and they were evidence of the breadth of the early labour movement, and of the major role the Left played in community life. Whilst socialism is often seen as based primarily upon economic theory there is a long tradition of thinkers who promoted more spiritual notions of community and fraternity as the key to a better world. One such of course was William Morris, who argued strongly that a successful revolution must be as much a moral revolution as an economic one.

Socialist Sunday schools also operated in other countries, notably the USA, but also in Australia, Canada, Hungary, Belgium, Switzerland and here in New Zealand.

Socialist Sunday Schools in New Zealand

Although Socialist Sunday Schools arrived in New Zealand much later than elsewhere, the press had already shown considerable interest in their operation in the UK and evinced considerable hostility to them. An editorial in the Auckland Star is not untypical. Socialism, it said, refused to accord respect to either constitutional or religious authority, and Socialist Sunday Schools preached ‘the doctrines of a violent social revolution’ in their catechism. This publication was a ‘deliberate incitation to revolution and anarchy, robbery and murder.’ (5 September 1907, p.4)

The first Socialist Sunday School in New Zealand was established by the Socialist Party in Dunedin in 1908, operating out of The Trades Hall. The Evening Star reported at some length about what was taught in the school (7 September 1908, p.6):

It was explained that the children would not be taught anything about the

hereafter, about which they had no definite knowledge, but they would be

taught how to live and be happy, and that the best way to be happy was to

make other people happy…They would teach them that the world had

sufficient to satisfy the needs of all, and that when they grew up they must

fight to remove wrongs that prevented people from being happy and

contented and loving one another. They would have placed before them all

the great thoughts from every thinker and would be taught to be guided by

reason. The scholars saluted the Red Flag, which they were told was the symbol

of Humanity, Love, Peace, Order, and Truth.

The Dunedin Socialist Sunday School was clearly firmly in the ethical tradition of its counterparts in the UK. The New Zealand Times suggested at the end of the year that the movement was spreading rapidly, with Auckland now also established and Wellington due to open early in the New Year. The paper also printed the Socialist 10 Commandments for the information of its readers. (12 December 1908, p.5) Wellington did indeed commence operations in February 1909, with classes taking place in the Socialist Hall in Manners Street. However, that was the extent of this ‘rapid’ growth, and no further Socialist Sunday Schools were reported until February1912, when the Maoriland Worker informed its readers that one had been formed at Waihi (16 February 1912, p.1) and that it was ‘making great headway’ (19 April 1912, p.12). Later in the year, during the great Waihi miners’ strike, the Waihi Socialist Sunday School was brought to the attention of Premier Massey in the House of Representatives. He was told that ‘an alleged Socialist Sunday School’ was being conducted in Waihi by an American, who had told his students that it was in the ‘workers’ interest to do as much damage as possible to their employers’ property.’ This American was probably the Canadian Wobbly (member of the IWW) John Benjamin King. ‘Could he not be deported?’ asked Representative A. Harris of Watemata. Clearly the Waihi school was preaching a much more militant brand of socialism than those elsewhere. The Waihi school did not survive the strike, and there is little evidence to suggest that Dunedin and Wellington were long-lived either. The Auckland Socialist Sunday School, however, was still thriving in 1913, and the press was still attacking the movement. In Socialist Sunday Schools, said the Inangahua Times, ‘the gospel of hate is being systematically taught by Socialists to children’ (11 November 1913, p.3) whilst the Grey River Argus said they were preaching ‘the religion of disobedience.’ (19 February 1914, p.2) The outbreak of World War 1 led to the cessation of all SSS activity.

In the aftermath of the war three Socialist Sunday Schools emerged. The first was in Christchurch, where the anti-war/anti-conscription movement had been strongest. Indeed, conscientious objectors were prominent in the teaching there, and the Head of the School was the Reverend J.H.G. Chapple, immortalised as Plumb in the novel by Maurice Gee. The school was launched in January 1918 and it is hardly surprising that one newspaper reported some ‘cranky-headed socialists’ were teaching their pupils to refuse compulsory military training. When two of them did so as it as it was ‘contrary to their religion ’their request for exemption was turned down, as the Socialist Sunday School was deemed an educational not a religious institution. (New Zealand Truth, 9 December 1922, p.7) Chapple explained the work of the School thus:

we have no bible teaching, he said, and we put Socialist teaching in the place of religious teaching…So-called Socialist ideals are in the very best sense religious. Teach them how to think and not what to think…On all sides enlightened Catholics and Protestants alike are dubious about the prevailing superstitions indoctrinated into the minds of their children, and in the Socialist Sunday School they could both find a common meeting place.’

(Manawatu Evening Standard, 8 September 1919, p.4)

Chapple courted further controversy at a May Day meeting in Christchurch in 1925, when he said he ‘would as soon pray for a weasel as a king’, which of course gave further ammunition to critics of the schools. The Christchurch School broke new ground with the publication of its own newspaper, The International Sunbeam, in June 1923, to counteract what it called the ‘untruthful statements’ being made about the Socialist Sunday School movement. In November 1924 it reported that the senior class was having lectures on psycho-analysis, and that it had debated the suggestion ‘That a change to a better order of society cannot come about except through the use of force.’ A new idea was mooted, ‘because it makes you think, and when you begin to THINK you become dangerous to the system under which we live.’ This idea was to write a question on the board for pupils to respond to, questions such as ‘What would I do if I was Prime Minister?’, ‘What would I do with £100,000 for public benefit?’

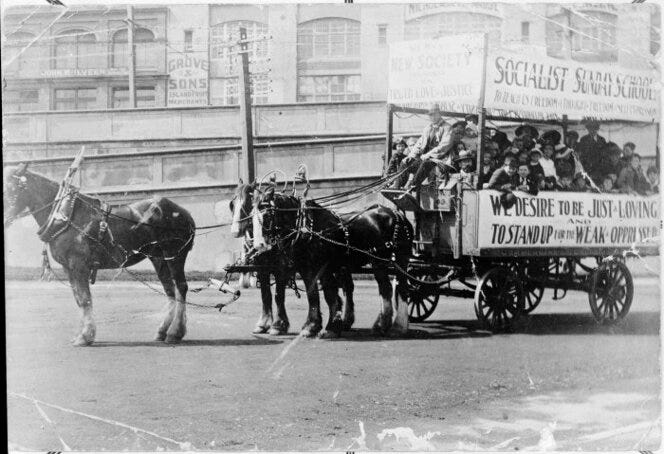

Auckland commenced operations in May 1920, and during the May Day celebrations in 1923 proclaimed that it had carried out the first baby dedication (a substitute for a christening) in New Zealand, although this was common practice in the UK and other socialist schools. The Palmerston North Socialist Sunday School was opened in September 1920. On the occasion of its first anniversary it reported that:

Every Sunday the Sunbeams have the glorious gospel of Socialism explained to them…We emphasise the spirit of internationalism…Socialist songs are sung every Sunday, the “Red Flag” never being omitted…we have just started the teaching of the international language—Esperanto.

(Maoriland Worker, 14 December 1921, p.5)

Other subjects taught included astronomy and evolution, whilst younger children focused on play, for example modelling with plasticine . The ethos of the three schools can be seen in the declaration read out at the start of each meeting:

We desire to be just and loving to all men and women, to work together as brothers and sisters, to be kind to every living creature, and to help to form a new society with Justice for its foundation and love for its law.

Three Socialist Sunday Schools, and yet in the early and mid-1920s they were subjected to a huge amount of press vitriol and a concerted campaign of vilification by organisations such as The Welfare League, The Political Reform League, the Orange Lodge, and even the National Council of Women. They were accused of blasphemy, of irreligion, of ‘pacifist lunacy’, of filling the minds of the young with communist ideas. Under much cover of sentimental talk, said one newspaper, they were inculcating class hatred. According to the Hawera and Normanby Star they were ‘a very serious menace to the Empire and a very direct challenge to the very foundations of civilisation.’ (3 August 1922, p.4) A widely distributed pamphlet, Warring against Christianity, argued that ‘true Britishers’ were proud that their nation had been built upon the foundations of Christianity. ‘Our forefathers’, it proclaimed, ‘had fought many bloody battles for the cause of righteousness’, but Socialist Sunday Schools ‘will assuredly make for the destruction of modern government and the fabric of modern society.’ The schools and their teachers were compared to lepers, to the typhus bacillus, and to the bubonic plague.

Why was such an insignificant movement subjected to such abuse? The reason was clearly rising support for the Labour Party. The campaign was a deliberate attempt, and particularly during election campaigns, to smear the Labour Party and discredit it in the eyes of the public, even though the Party was in no way connected to the Socialist School movement. The Reverend Leonard Isitt, Liberal MP for Christchurch North, admitted as much when he urged his fellow Liberal and also Reform MPs to wake up before it was too late and counteract the propaganda of organisations such as the Socialist Sunday Schools. In May 1921 the Minister of Education, C.J. Parr, ordered compulsory weekly flag-saluting in schools in order, he said, to counter disruptive influences such as the Socialist Sunday Schools. There are two clear examples of this smear campaign. First, the aforementioned pamphlet, Warring Against Christianity, was published by the Newsletter in Wellington, which claimed to be the organ of the Reform Party. Ted Howard, Labour MP for Christchurch South, raised the matter of its circulation during a Dunedin North by-election in the House of Representatives, calling it a ‘disgrace to politics.’ Secondly the Grand Master of the Orange Order, the Reverend G. Knowles Smith, speaking at a Grand Orange Lodge meeting in Auckland Town Hall early in 1912, accused teachers at the Auckland Socialist Sunday School of a ‘blasphemous parody’ of the hymn Onward Christian Soldiers, quoting the following verse:

Onward Christian Soldiers, duty’s call is plain,

Slay your Christian brothers, or yourselves be slain,

Pulpiteers are spouting effervescent swill,

In the name of Christ they call you to rob, and rape, and kill.

This was, in fact, nowhere to be found in any New Zealand Socialist Schools’ hymn book. It was taken from that of the Sydney Socialist Sunday School hymn book, a school run under the auspices of the Communist Party, and analogous to the proletarian Sunday schools of the Communist Party in the UK. This was a deliberate attempt to connect the Labour Party to Socialist Sunday Schools and thus to the Communist Party.

Unfortunately, they had an effect. The Palmerston North School was forced to close its doors at the end of 1922 after a concerted campaign of opposition. Auckland continued, but there is no report of activity after the mid -1920s. Only Christchurch survived into the 1930s. A correspondent to the Press suggested that ‘The whole world is surely suffering enough without the rising generation being instructed how to sing the “Red Flag” and to carry out “the duty of children to destroy the present-day economic condition.”’ (3 June 1932, p.13) The Auckland Star reported in May 1932 that it had been re-launched by the Socialist Party there as the Socialist Guild of Youth , the reason given that it wished to avoid any confusion with the church Sunday Schools.(31 May 1932)However, there is one school that I have not mentioned, one that was distinctly different to the other, ethical socialist schools, avowedly and proudly communist, and that was the Blackball Socialist Sunday School.

Young Comrades—The Blackball Socialist Sunday School.

The Communist Party of New Zealand had moved its headquarters to the coal fields of the West Coast, to Blackball, in 1925. Blackball, scene of the famous ‘crib strike’ of 1908 and birthplace of the ‘Red Feds’, was the home of Bill Balderstone, a radical trade unionist and Communist Party member. Communists and socialists alike saw teachers and schools as purveyors of capitalist ideology, and in 1927 they organised a children’s league, ‘The Young Comrades.’ It was modelled on the Socialist Sunday School and met at the home of Bill and Annie Balderstone on Wednesday evenings and Sunday afternoons. Unlike its counterparts in Auckland, Palmerston North and Christchurch, however, it preached class war.

The organisation produced a newspaper, The Young Comrade, which certainly ran from July 1927 until March 1929[i], and which children sold for a penny before Sunday evening cinema shows and outside the Miners’ Hall after union meetings. Copies also circulated in Auckland. The objective of the paper was to help children ‘pick out the lies and to recognise the truth in the daily newspapers.’ (The Young Comrade 1 December 1928, p.1) It presented communism as a superior form of social organisation, comparing ‘village life’ in New Zealand and Russia. The November 1927 issue was advertised as a 6- page special edition ‘News from Workers’ Russia’. Imperialism, with its constant search for new markets, represented capitalism driving on towards its inevitable collapse, and New Zealand’s subjugation of Samoa was used as an example. Capitalism’s unceasing search for profit was seen as the cause of the relentless misery of the workplace. One correspondent, signing himself ‘Yours for the revolt, Jack Wild’, complained about an education system which forced him to salute the Union Jack. He urged young comrades to set aside a day every year and refuse to go to school ‘as a protest against the system that forces us to leave school and go to work when we are 14.’ (Sun, 12 June 1929, p.1)[ii] In particular the paper mounted an unceasing campaign against militarism, attacking Anzac Day as a glorification of war, and the Boy Scouts as a blatant attempt to prepare the young for war. Letters were exchanged with young comrades in Britain, Australia and Russia. All members wore red badges with the hammer and sickle, and the last extant issue of the paper reported that they were planning to adopt a navy- blue uniform with red necktie like the Pioneers in Russia.

Socialist Sunday Schools were a very minor and relatively short-lived phenomenon in New Zealand. With the exception of Blackball, they followed the ethical tradition of those in Great Britain. Whilst they were established to counter what socialists saw as the capitalist and religious propaganda of the state school classrooms, they also attempted to offer a broader and more interesting curriculum to their students. They were part of the socialist attempt to create an alternative, all-embracing community life for their members and their families. The violent opposition they aroused here demonstrated just how much of a threat to ‘traditional values’ they were perceived to be.

[i] The 7 existing issues of The Young Comrade are in the George Griffin Papers in the Alexander Turnbull Library, 86-043-2/03

[ii] This letter is not in any of the surviving issues of The Young Comrade so it either appeared in a missing issue OR it suggests that there were further issues after March 1929

A great story. The Socialist Sunday Schools certainly did not deserve the opprobrium directed at them by the colonialist establishment, and their teachings had a moral quality that was absent from colonialist propaganda.

However the problem with the SSS teachings, and all socialist teaching based on the idea that the ultimate purpose in life is happiness ("they would be taught how to live and be happy, and that the best way to be happy was to make other people happy") is that there is more than one way to happiness and capitalists are just as capable of making the claim that they have "the best way to happiness". Elon Musk, for example, doubtless accepts the principle that "the best way to be happy was to make other people happy" and his means to that end are X, SpaceX, Tesla, Donald Trump and so on. We can debate the particular merits of each of his offerings but the point is that giving people what they want (or think they want) is not the way to a better world.

The United States was founded as a secular society dedicated to "the pursuit of happiness" yet it is a state that has brought untold grief to the earth and will yet harvest the bitter fruit of what it has sowed.

The truth, therefore, is more complex and contradictory than is allowed for in Marxist ideology. While we all desire to be happy, neither the pursuit of happiness nor "making others happy" should be our ultimate goal in life.

The flaws inherent in the simplistic approach of the SSS would have been apparent even to the children who attended. They would have understood that it is not strictly true that "all the good things in life are produced by labour". Are commodities the only good things in life? What about the sea and the sky, the bush and all the plants and animals that fill the earth beyond the reach of mankind?

Is it true that "whoever enjoys (commodities) without working for them is stealing"? Children know that they and their beloved grandparents enjoy the fruits of other's labour, yet there is no guilt attached. Still, on balance the SSS were a positive counterweight to colonialist propaganda. Reverend Chapple's remark that "So-called Socialist ideals are in the very best sense religious. Teach them how to think and not what to think…" remains valid today.

Beautifully written article about an aspect of our social/ political history that we know so little about. The fanatical opposition to the schools makes highly amusing reading today. I wonder how much, if any, of it was based on actual knowledge and experience of sitting in on an SSS while it convened, and observing the kids (modelling Lenin no doubt) with their Plasticine!