Our History: The Socialist Church

Martin Crick writes on one of the earliest socialist organisations in New Zealand. First published October 2022 for volume two of The Commonweal.

The Christchurch Socialist Church was the first overtly socialist organisation in New Zealand, although a Fabian Society was in existence slightly earlier. It was founded in May 1896 by Harry Atkinson, whom Bert Roth has called ‘the father of New Zealand Socialism.’ He was the nephew of the former Premier Sir Harry Atkinson. An autodidact who read the likes of Kropotkin, Stepniak, Edward Carpenter, Thoreau and the Fabian Essays, Atkinson spent three years in England from 1890. There, in 1892, he joined the Labour Church movement established by John Trevor, a former Unitarian minister. Trevor saw God as working through the labour movement: ‘the great religious movement of our times is the emancipation of labour’, he said. Atkinson became the secretary of the movement, and the publisher of its journal, The Labour Prophet. He was also exposed to the ideas of Robert Blatchford and the Clarion movement, and helped to form the Independent Labour Party (ILP).

Atkinson moved back to New Zealand in November 1893, arriving the day after the general election that saw Richard Seddon elected as Premier, and to a country in the process of a significant legislative programme of social and industrial reforms. He found employment at the Addington Railway Workshops in Christchurch, before founding the Socialist Church. It differed from Trevor’s Labour Church in that Atkinson saw socialism itself as a religion. Shortly before his death he said that to him ‘Socialism was not a set of dogmas but a living principle, a striving after human betterment under all circumstances.’ The Church’s prime object was to promote ‘ a fellowship amongst those working for the organisation of Society on a basis of Brotherhood and Equality.’ It affirmed the principle that ‘only as we learn to lead purer and better lives can we benefit by any measures of social reform.’ This is very much the ethical socialism that underpinned the Clarion movement and the ILP in Great Britain. The Socialist Church emphasised associational activity and self-education.

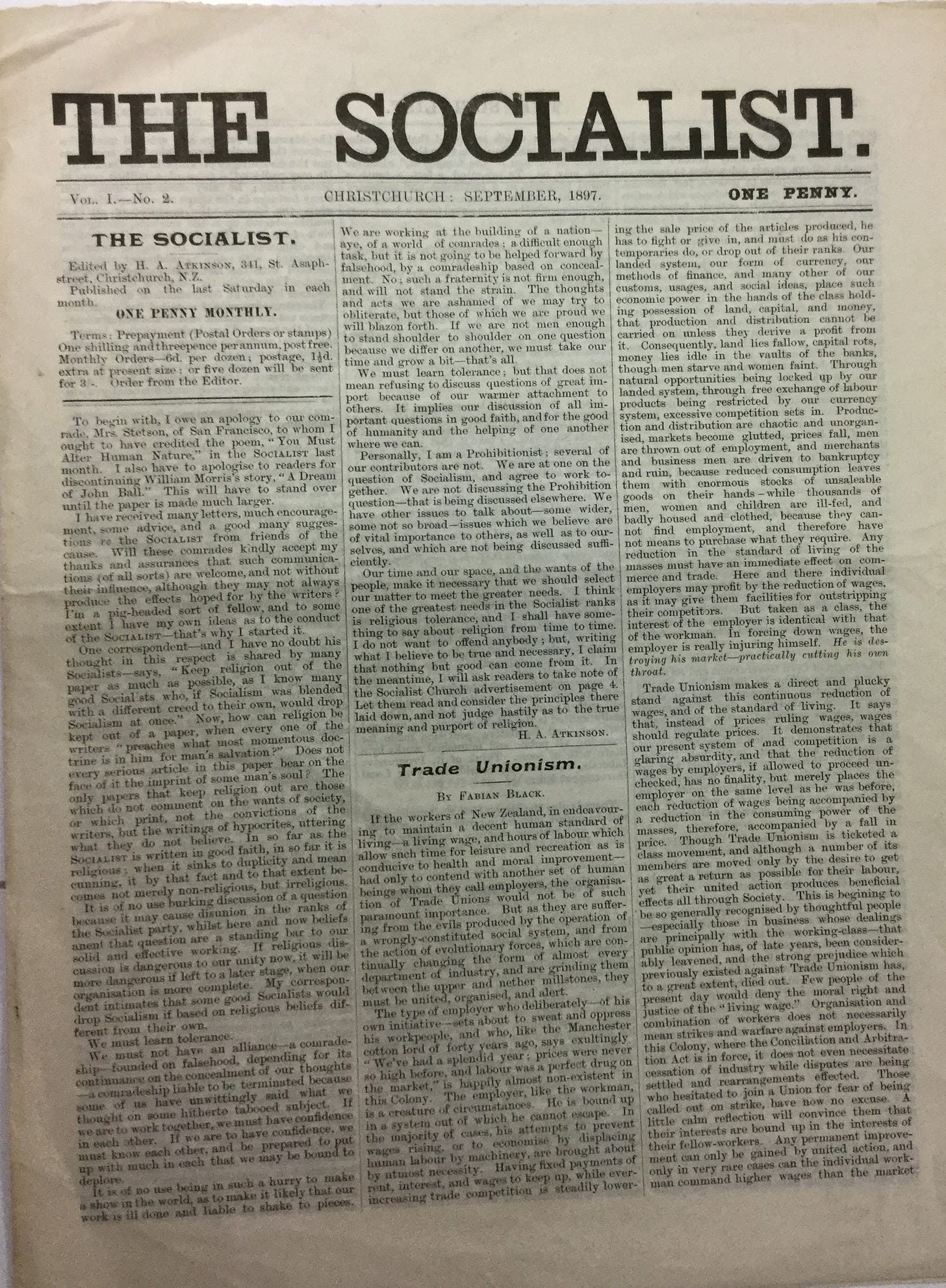

Members met weekly to listen to a range of speakers or to discuss a wide variety of literature. Speakers included the visiting English socialist Ben Tillett, the maverick professor of Chemistry Alexander Bickerton, described by Jim McAloon as an anarchist, and members of the local women’s movement such as Eveline Cunnington, Christina Henderson and Louisa Blake. Cunnington argued that socialism was the economic interpretation of the teaching of Christ, Henderson that the capitalist system was ‘the most unjust that the mind of man could have conceived’, whilst Blake promoted free and compulsory technical education, with ‘all industries being protected for the benefit of the workers by the State.’ Literature studied included Marx’s Capital and the Fabian Essays. Open-air meetings were held every Sunday afternoon in Cathedral Square, and a short-lived journal, The Socialist, was published between August and October 1897.

By 1899 the Socialist Church was relatively successful, and growing in numbers. A notable recruit was Jack McCullough who was to become, says Jim McAloon, ‘the single most influential figure in Christchurch socialism of the period.’ It suffered a temporary setback when it became one of the few groups to oppose the Boer War, arousing much ill-feeling amongst a patriotic public, but one positive was the recruitment of Jim Thorn, who volunteered to fight in the war but returned disillusioned and a convinced pacifist. He too went on to become a leading light in the labour movement, and he left us one of the few contemporary records of a Socialist Church meeting. It was, he said, ‘a queer mixture of atheists, Fabian socialists and radicals, all of them idealists... Having read a very excellent (as I thought) paper, I was treated to some ferocious criticism, and got the impression that I had strayed into a hornets nest of very angry and disagreeable people. It was a sort of baptism of fire, a running of the gauntlet.’

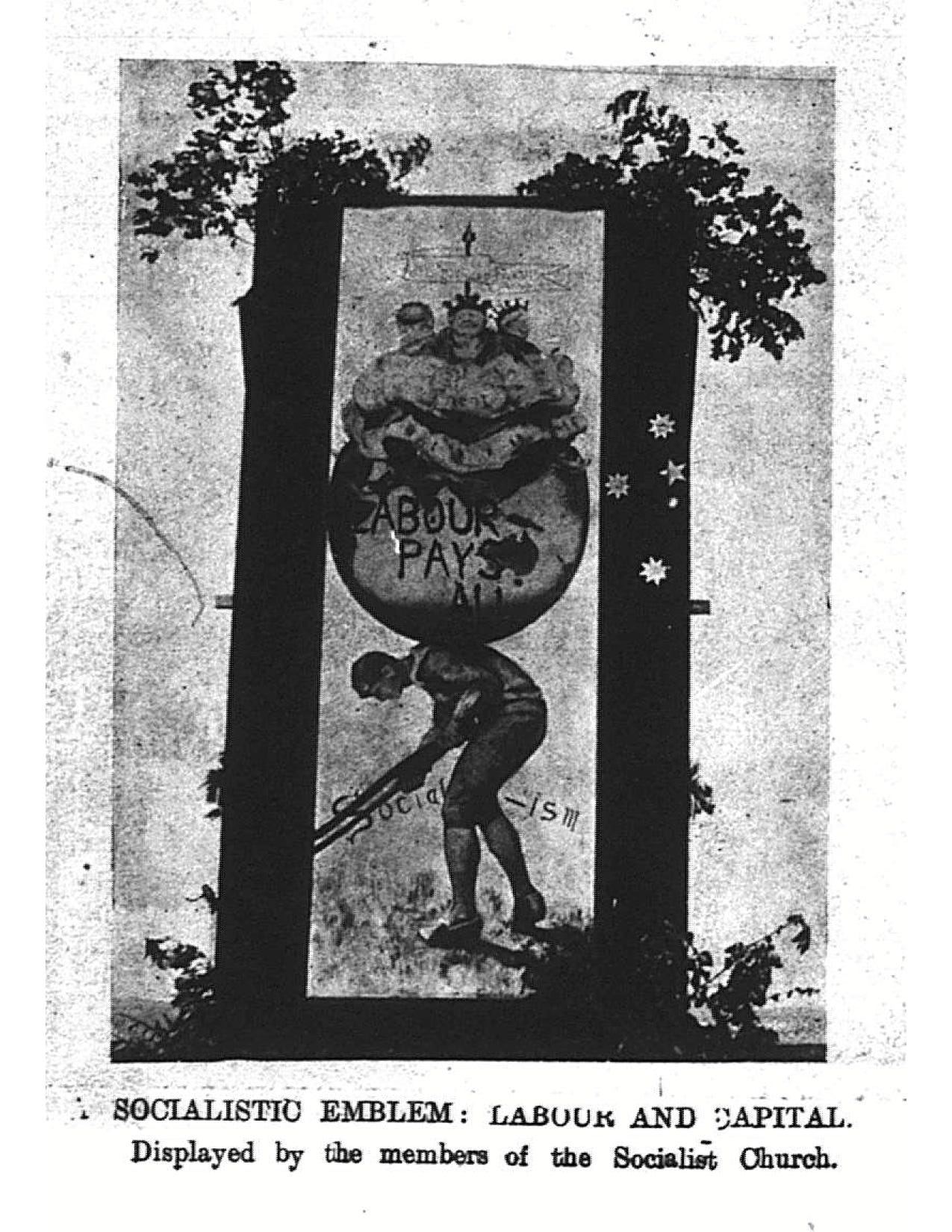

The Socialist Church promoted a range of ideas: old age pensions, state control of industry, municipal reform. It was almost a lone voice in criticising the Liberal government, giving an insider view of the so-called State Socialism in New Zealand, attacking the arbitration system and the levels of inequality. It achieved some notoriety on Labour Day 1901 with its attack on the capitalist system (see p.?) However, it ceased to exist in mid-1905. Atkinson suggested depleted finances and changing priorities as the reasons for its demise, but a more likely explanation is the arrival on the scene of the New Zealand Socialist Party, formed in 1901 and with a Christchurch branch commencing operations in January 1902. What then was the significance of the Socialist Church?

According to Bert Roth it was important because it attracted numerous professional people to its ranks at a time when the labour movement elsewhere was confined almost entirely to manual workers. Equally importantly, in my opinion, it was instrumental in the formation of a socialist sub-culture in Christchurch through its educational activities and its social events such as picnics, dances and teas. And above all it was the first openly socialist organisation in New Zealand, and the first to call for an independent labour party; it began the shift away from the dominant liberal progressivism and lib-lab alliance of the late 1890s.