The Alliance – a political tragedy (part 1 of 2).

Victor Billot writes on his experience of the NewLabour and then Alliance parties. This is the first of two parts, published in Commonweal volume four in October 2023.

I was a founding member of the NewLabour Party and then the Alliance. I was a member through to the Alliance’s deregistration in 2015 (although the party never formally dissolved.) apart from a brief lapse in my membership when I was attending journalism school in 2002.

In the years when the Alliance was doing well in the 1990s I was a loyal foot soldier. Later on, after the Alliance disintegrated and left Parliament, I found myself promoted to senior positions and stood several times in elections, generally polling poorly. My commitment could not be questioned, but my timing was not so good.

To be honest, my Alliance experience was not a good one. I don’t regret it but I do think there are many lessons to be learned. Unfortunately, those lessons are mainly negative ones. When I entitled this article a “political tragedy” this is not cynical humour. The tragedy of the Alliance is the tragedy of the New Zealand left (and the state of our society) and over the years since its defeat and decline, I have often had moments to wonder – what if things had been different?

The Alliance was the last attempt to build a genuine social- democratic mass party in New Zealand. I don’t think there is anything directly comparable in the English-speaking countries. The Alliance failed, or rather was wrecked by a series of poor strategic decisions. But these decisions were made in the context of and under pressure from the hostile environment it operated in, or perhaps particular features of New Zealand politics and MMP power politics that proved too hard to navigate.

There were several distinct periods in the history of the Alliance. This article is a broad-brush report from my perspective of the Alliance’s first three phases – the New Labour Party (NLP) prelude, the pre MMP Alliance, and the post MMP Alliance and time in Government. I will follow in a future article the post-Parliament decline of the Alliance. My account here is a highly compressed one.

The first period of the ‘Rebel Alliance’ was the ‘prequel’ of the series (I will end the Star Wars metaphors here.) This was the foundation of the NewLabour Party (NLP) in 1989 as a left wing split from the deeply dysfunctional Labour Party of the late 1980s. The NLP people were always the core of the Alliance. The Green Party was formed in 1990, and was a founding constituent party of the Alliance, but left the Alliance in 1997. You could say the Green Party has been more successful, in that it is still a functioning minor party, but these days it seems to be something of a pale shadow of its former colourful self. Anyway, that story is for others to tell.

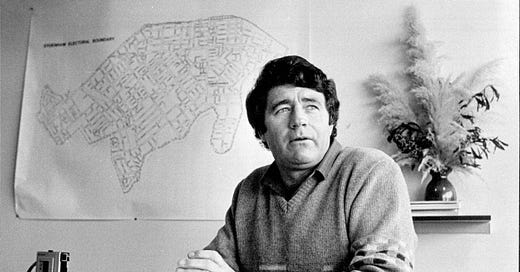

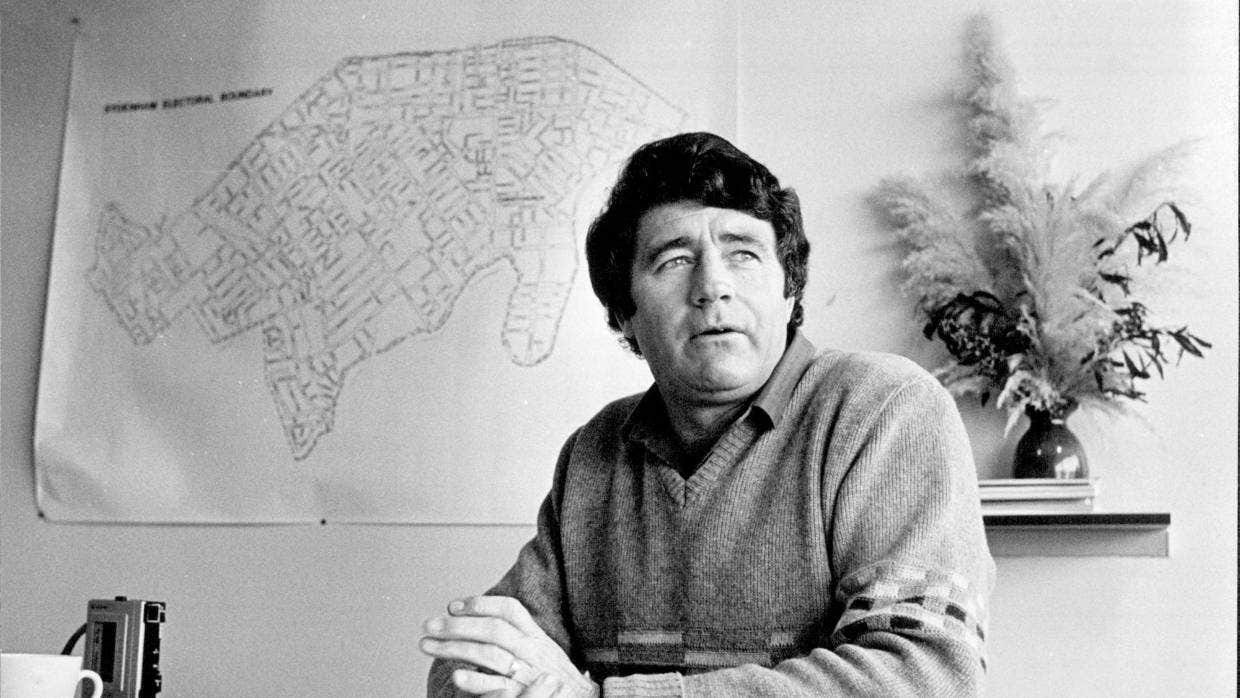

The NLP was dominated by a few big personalities. Jim Anderton was its greatest asset and eventually its biggest flaw. A sitting MP, ambitious and extremely dogged, Jim left the Labour Party in 1989 after several years of battling against the Rogernomics faction during the Fourth Labour Government. His strong personality probably gave him the ability to survive all this, but it was also to be something of an Achilles Heel.

As a credible figure and a popular local MP, Jim managed to retain his Sydenham seat in the 1990 election. In pre MMP days this was the only shot at getting Parliamentary representation. The NLP was dominated by Jim, as he was the only MP, and the Party depended on him for its existence. On the other hand, Party President Matt McCarten was a youthful and impressive organizer who formed an effective team with Jim. Jim was a Catholic, an ex-businessman, a traditional social- democrat with traditional values and principles. Matt was a mercurial socialist who had come up the hard way and established himself as a blue-collar union organizer. Later on, this unusual but effective relationship would sour.

Meanwhile, I was one of a group of young people who got sucked into politics at the time. Many of the people I remember from that era have gone on to do sometimes impressive and sometimes interesting things, which I suppose is not surprising considering how small New Zealand society is. I was politicised at high school. My family was what I would describe as respectable working class but some bad experiences for my parents with employers had focused my mind on the ugly realities of capitalism. As a young University student, I was aware of class differences with the middle class or even wealthy background of many of my contemporaries. I joined what was at that point a volatile scene.

Out of curiosity, I attended a protest of leftists outside the Labour Party conference in Dunedin in 1988. Jim Anderton had narrowly lost out to Ruth Dyson on his bitterly contested challenge for Party President from the left. He came out to address the crowd and some misguided individual threw an egg at him. I bought a copy of the Peoples Voice. It was an exciting evening. Within a few months, Anderton announced he was leaving Labour and starting the New Labour Party. I recall the first NLP meeting in Dunedin in the YWCA Hall, probably around May 1989. I went with my dad. The room was filled with rows of solid and serious middle- aged blokes. It was an old school Dunedin working- class crowd, something that you don’t really see anymore. Jim spoke and received a positive response.

The next few meetings, without Jim, were smaller. They seemed to involve union organisers arguing with one another. Chris Trotter was one of the leading lights. It all went above my head at this point, although I was learning that the worst arguments in politics are those between people on the same side. I started going around handing out leaflets and even canvassing. It was an interesting experience. I realised there were a lot of lonely people out there living quiet forgotten lives, who would haul me inside for a cup of tea. They were often only politely interested in politics. It was just a chance for them to talk to someone.

I also spent some time honing my debating and heckling skills. I must have been quite intolerable and self-righteous, but the people I was annoying deserved it all. At one public meeting at the Otago Polytechnic, the lame duck Labour PM Mike Moore was giving a speech. He blathered on and in question time I jumped up in my seventeen year old fury and denounced his Government for selling out the working class. He offered some weak reply – something about the share market bouncing back or something. ‘But I don’t have any shares’, I yelled back. ‘That’s a bit below the belt’, he replied in a hurt tone. The crowd hooted with laughter, and I saw the glare of the local Labour MP Pete Hodgson boring into me.

This was a revelation. I had argued with the Prime Minister – and I had the distinct feeling I had come off best. Whether or not this epiphany did me any good is another question. I had a later encounter with David Lange, after he had resigned as Prime Minister. It was a vaguely sad afternoon. He had been a national hero a few short years ago – the man who had got rid of Piggy Muldoon. This lunchtime there wasn’t a big crowd and when I argued with him about the harm of Rogernomics he rebutted me but his heart didn’t seem to be in it. He referred to me as ‘John the Baptist’ over there,” which I have always recalled as an odd insult and perhaps not much of an insult at all from the former Methodist lay preacher.

We got through the 1990 election. Labour was trounced. Jim Anderton was back in but we had not done that well in the overall party vote with just over 5%. The victorious National Party had promised a ‘decent society’ but aggressively extended the neoliberal right -wing agenda of the Rogernomes. Unemployment soared; benefits were cut. The Employment Contracts Act smashed the union movement, wages and conditions were ravaged, and it left workers stunned and disoriented. Privatisation continued. Even traditional conservative rural communities were left reeling. In a very short time frame, power and control had shifted.

It was obvious that none of the smaller parties were going to get into Parliament with the First Past the Post voting system creating an effective duopoly. The lesson was provided by Social Credit, which had peaked at over 20% of the vote in the early 1980s but had only 2 MPs to show for it (one of them, Gary Knapp, beat a National candidate by the name of Don Brash.)

Thus the Alliance was born. It brought together unlikely bedfellows – the NewLabour Party and the Green Party, the Democrats (formerly Social Credit), Mana Motuhake, and a little later the Liberal Party, which was comprised of two middle of the road National MPs horrified by the extreme lurch to the right of the National Government (they later decamped to NZ First). The Democrats by this stage had passed their peak. They represented a conservative force in the Alliance, but also brought a network in the provinces and a large war chest. Mana Motuhake was a sort of precursor to Te Pati Māori, led by former Labour MP Matt Rata who had been unable to break the Labour hold on the Māori electorates.

From the beginning the Alliance was a marriage of convenience. It was there to unite the forces outside Labour and National and bypass the electoral grip they held. But it did have a political logic – it was made up of all the forces opposed to the ‘New Right economic revolution. The Alliance was defined by what it was against. It managed to cook up a manifesto that presented a social- democratic, managed and mixed economy model, that sought to redistribute wealth and rebuild the welfare state. It was not socialist, but most socialists (outside the revolutionary fringe) saw it as the best option, even as a defensive step against the rapidly advancing free market agenda.

While the Alliance was seen as the challenger from the left, in 1993 Winston Peters broke off from National to form New Zealand First. I always interpreted Peters as a Muldoonist if anything, with a gift for attracting the discontented but politically naive with empty slogans and manufactured outrage. He is still doing it in 2023, a remarkable achievement of longevity if nothing else. For periods in the past he tacked to the left, attacking finance capital in the 1990s (remember the Winebox Inquiry) and at one stage in 1996 NZ First somehow won some of the Māori electorates (not likely these days).

In this early 1990s period the Alliance did very well. It outpolled Labour in by- elections in Tamaki, the King Country and Selwyn, none of which were left leaning electorates. The Alliance actually seemed to do better in the provincial centres. The Pasifika vote stayed largely with Labour if I recall correctly, despite all the damage free market policies had wreaked on urban working- class communities. In the 1993 election, the Alliance hit its high point. Still only gaining two MPs, it nonetheless had built a large active membership. Dunedin North had one of the biggest and most left -wing Alliance branches, whose membership included latter day Socialist Society members such as Quentin Findlay and Chris Ford, as well as the late Professor Jim Flynn, and many others who have had an impact in one way or another over the years. At this point I understood the plan was to replace the Labour Party, by then regrouping under the centrist leadership of Helen Clark. The hard right -wing faction of Labour, including Douglas and Prebble, had broken off into ACT, but at this point they had little support, as the National Party was basically doing their job for them.

The big push in 1993 was for the referendum on the electoral system. The driving forces behind the right -wing shift in New Zealand society – aggressively ideological capitalists and private sector management – threw everything into opposing MMP, and so did the two main parties. Ironically, they needn’t have worried too much. The right -wing economic ideology was already baked in and, with a few minor tweaks, we are still living under it today. However, MMP got across the line, and the electoral game was changed for the Alliance.

The next ‘third period’ therefore was this post MMP era which saw the Alliance in Government by 1999. The 1996 election saw one big plus – a large group of MPs were elected on the list. But the overall Alliance vote was dropping as the Labour Party reasserted itself. Around this time I was working for unions. I recall the loathing the Labour and Alliance factions had for each other, and I occasionally got a spray myself. I have a rather long memory, and this colours my view on the Labour Party right up to today. There is an amazing sense of entitlement and aggressive patch protection that exists in its ranks. But at the top level, practical considerations overcame any personal differences. In these conditions, it was obvious a united front of Labour and Alliance was the only way to get the numbers to remove National (that was how it was sold anyway.) In 1999, I came back early from my OE to help with the campaign. The united strategy was successful in that National was thrown out. But it was a disaster for the Alliance in the long term.

As the junior coalition partner, the Alliance was trapped in a supporting role. The Alliance was always made up of people who had strong principles and beliefs. Sometimes this shaded off into eccentricity. But you never questioned their sincerity. Party members saw themselves as directing their MPs as representatives of the party. Jim on the other hand saw the role of members as to campaign in elections and leave the politics to him (this may be a little simplistic but not too remote from the truth.)

In 2001 things came to a head and there was a cataclysmic split. The ostensible reason was New Zealand’s involvement in supporting the war in Afghanistan. Anderton’s line was the Alliance was in a coalition Government and bound by collective cabinet responsibility. Much of the party membership disagreed. They hadn’t come this far to provide cover for the Labour Party and its compromised establishment politics. This was the flash point for building tensions in the Alliance over the direction and processes of the party. Jim Anderton had grown increasingly domineering in his leadership and had bluntly put down those who saw the Alliance being submerged into the Labour Government. At the same time there were machinations and factions within the Parliamentary staff and senior leadership (members such as myself were largely on the outside of the intrigue.)

The resulting split saw a very confused division. I recall attending a membership meeting in Wellington where I was living at the time which literally melted down when MP Sandra Lee and Party President Matt McCarten were at the top table swearing at each other. It was an absolutely terrible experience. After the split, the Alliance leadership passed to Laila Harre. However, she did not manage to get across the line in her West Auckland electorate in the 2002 election, and the Alliance party vote collapsed. Anderton remained in Parliament and created a new vehicle, the Progressive Party. It survived for a while but had very little reason for existence as it was operating as a clip on to the Labour Party. The Progressives vanished a few years later and their members were absorbed into the Labour Party.

The above is just a potted history with some personal insights. In my next instalment, I would like to discuss the ‘fourth act’ of the Alliance tragedy – life after Parliament – and reflect on some of the weird dead ends the left have wandered down over the years. I will also be touching on two important questions. What can socialists learn from the Alliance? Is it possible to rebuild a similar party, or even desirable?