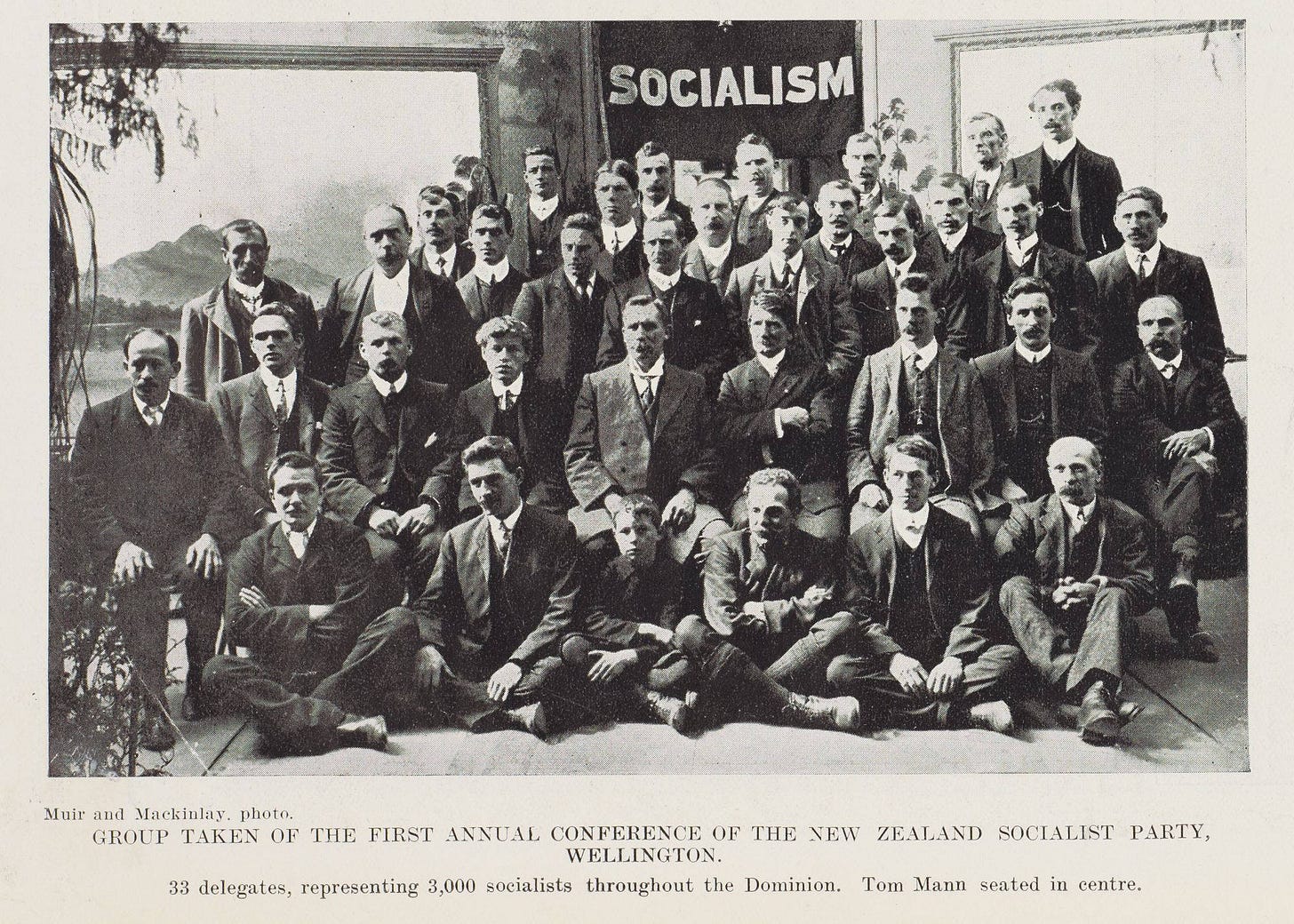

The New Zealand Socialist Party First Annual Conference 1908

Martin Crick on the first conference of the New Zealand Socialist. First published in volume for of The Commonweal in October 2023.

The New Zealand Socialist Party held its first annual conference in Wellington on Easter Monday 1908, almost 7 years after its foundation. That hiatus mirrors almost exactly the trajectory of the NZFSS. For much of that period it had only three functioning branches, Wellington, Auckland and Christchurch, with Wellington by far the most active. These branches were largely autonomous. Again, we see distinct similarities between the NZSP in its early years and the Federation. A further point of convergence lies in the fact that the Wellington branch launched a journal, Commonweal, in February 1903. In its first iteration this lasted until September 1904.

However, between 1906 and 1908 the NZSP experienced a rapid growth in membership. This was partly due to increasing trade union disillusion with the conciliation and arbitration system. The Auckland tram workers’ strike in November 1906 was the first in New Zealand for 12 years. As it was the only political party hostile to the Arbitration Act the Socialist Party began to attract more militant trade unionists. New branches in the West Coast mining towns were inspired by the arrival of a workers with a background in North American or Australian industrial unionism, men like Pat Hickey and Paddy Webb. Meanwhile in Wellington the arrival in 1906 of Canadian H M Fitzgerald, a proponent of De Leonite industrial unionism, stimulated the movement there. He embarked on a tour of the West Coast which led to an explosion in the number of branches. Commonweal was restarted in September 1906, but now with a national focus. The Blackball Strike in 1908, initially over the issue of ‘crib time’, led to the sacking of Hickey and 6 others, all socialists, and further encouraged the movement.

The Party encompassed a range of views: ethical socialism, Marxism, anarchism. It was also divided over tactics, with many of the mining branches arguing for a focus on revolutionary unionism, building the one big union, a general strike to overthrow the capitalist system, whereas others supported participating in the political process and electing socialists into parliament. De Leonites advocated a dual strategy. Consequently, the party lacked a clear focus, and the time seemed ripe therefore for the Party to hold its first national conference to debate these issues. Again, the similarities between the NZSP and the NZFSS are apparent. We too embrace a range of theoretical and strategic viewpoints, we too are debating ‘the way forward’.

Much to the organisers’ surprise 33 delegates registered, claiming to represent 3,000 members. This of course we cannot match, operating in an entirely different context, where trade unions have been in retreat since the 1980s. Yes, there has been a surge of industrial action recently, but that has been largely amongst public sector workers, with little or no evidence of political underpinning. Nonetheless the discussions in 1908 around organising and strategy, and particularly the debate over the value of political action, standing socialist candidates in elections, is very pertinent to us, and the keynote speaker at our conference, Daniel Lopez from the Victorian Socialist Party, will surely help to focus our thoughts.

The NZSP confirmed its national platform as ‘The establishment in New Zealand of a Co-operative Commonwealth founded on the Socialisation of Land and Capital.’ The evening session on the Monday however revealed the confusion as to the Party’s direction. The newly elected National Executive had been instructed to draw up a manifesto stating its position on current political questions for use in the forthcoming general election. A motion from the floor argued that ‘The New Zealand Socialist Party take no political action at the present juncture’, one delegate suggesting that ‘It was a fallacy to think that they could obtain Socialism through parliament. It was only through the industrial field that their object would be obtained.’ Visiting British socialist Tom Mann (see below), well known to the New Zealand Socialist Party, and at that time organiser for the Victorian Socialist Party, told delegates that the IWW was ‘the greatest organisation of its kind in existence’. The motion was carried by a majority of two to one, and delegates adopted the preamble of the IWW. Mann also spoke of the progress of the socialist movement in Australia and it was agreed to affiliate to the Socialist Federation of Australasia, formed in June the previous year. The Party confirmed its opposition to arbitration and to militarism, and agreed that Commonweal should be the national organ of the Party.

Members later overturned the Conference decision on political action, and the Party stood four candidates in the general election that year. Nevertheless, the candidacies were largely propagandist, seeing elections as an opportunity for education and recruitment. What the conference had achieved was a national organisation with a central executive and branches, and a new set of rules. The following years saw increased industrial militancy and demands for an independent political labour movement. Militant miners formed the Federation of Labour (the ‘Red Feds), seeing industrial action via ‘one big union’ as the way to achieving socialism, whilst Trade Councils focused on building a political party. The NZSP saw itself as the political arm of the Federation. Defeat at Waihi in 1912 however, led the Federation to propose unity between the two wings of the working-class movement, which saw the formation of the Social Democratic Party in July 1913, forerunner of the Labour Party (1916). Only the Wellington branch of the NZSP stayed outside the new party, eventually merging into the Communist Party in 1921. During its short history the New Zealand Socialist Party had not achieved electoral success, but its propaganda and the ideas it promoted had influenced all parts of the labour movement and arguably moved it further to the left than it might otherwise have been.