The Oppressed Become the Oppressor: the Demise of the Jewish Radical Tradition in Israel

Andrew Tait explores the decline of radical political traditions and rise of Zionist reaction in Israel. First published in The Commonweal Volume 6, October 2024.

‘I arrived at the end of 1972. I imagined that I was landing in a socialist utopia. Instead, the reality of the Zionist project made itself explicit at the airport: European Jews stamped my passport, Middle Eastern Jews manned the luggage carousels, while Palestinians swept the floors and cleaned the toilets. So much for the socialist dream.’

—Lousie Adler

Ideas matter. This may seem a strange assertion in a world where Israel is able to massacre with impunity 40,000 people in a ghetto smaller in size than Wellington city. The only thing that seems to matter in international politics nowadays is military force.

But, as Italian revolutionary Antonio Gramsci argued, hegemony in the long run relies on both force and consent. Hitler was able to invade most of mainland Europe but his nightmare of a 1000-year Reich was doomed despite his military power because his ideology was so repugnant to so many. By contrast, the universalist ideals of the French Revolution, even when refracted through Napoleon’s empire, spread like wildfire and remade the world.

When it was founded, the Israeli state pretended to be part of that universalist project. This fraud meant Israel was, in theory, further to the left than any non-Soviet country but in reality it was a colonial settlement dependent on foreign powers. The socialist veneer not only helped integrate left-wing Jewish immigrants, it also gave protective colouring to Israel in the decolonisation struggles that swept the post-war world.

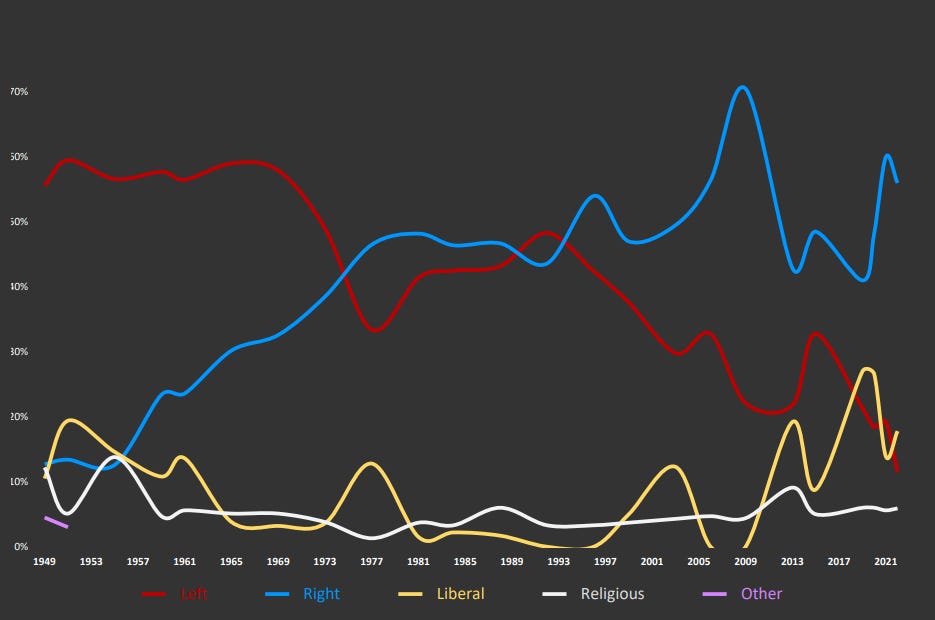

However, the socialist veneer was steadily eroded by the racist reality. Now the far-right calls the shots in Israel’s war cabinet. The simple explanation is that labels don’t matter—that the ‘socialists’ of Mapai are the same as the religious fascists of Otzma Yehudit (Jewish Power). This is partly true—there was no constitutional rupture because the state from its founding was dedicated to colonising Palestine. Warlords like Moshe Dayan could seamlessly transition from Labour to Likud because the main enemy was always Palestinian, never the Israeli working class. But although all the main currents of Zionism were for an apartheid state built on Palestinian land, dismissing the shift in ideology from left to right misses the demographic shifts that first gave Zionism its socialist colouring and then stripped it away, the brutalising impact of colonisation, and the role of ideology in struggle.

The triumph of right-wing Zionism over the course of the twentieth century required the erasure of another history—that of the radical Jewish tradition. The degeneration of ideology in Israel is instructive and The Radical Jewish Tradition: Revolutionaries, resistance fighters and firebrands (Interventions, Melbourne, 2024) by Donny Gluckstein and Janey Stone is a good guide[1]. This book tells the story of the radical Jewish working class from fighting pogroms in Russia, to rent strikes in New York and finally to the fraud of the Zionist state, where Labour Zionism provided an illusion of class struggle ‘to placate radical Jewish immigrants until they had adjusted their principles appropriately.’ (Gluckstein and Stone, p. 305).

Ethnic nationalism

The establishment of a national homeland for Jewish people in Palestine has been described as the last European colonial project, which is true, but Israel is a special case not only because of its late arrival. It is also unusual because it is colonialism by proxy, where first the UK and then the USA sponsored Jewish colonisation of Palestine, and because of the central role antisemitism plays in European nationalism.

The zenith of European colonialism, the Scramble for Africa, followed the Berlin Conference of 1884, as mass production of weapons like the Maxim gun finally gave the West decisive military superiority globally. The triumph of capitalism and European imperialism gave birth simultaneously to its opposite—the international working-class movement; May Day was reborn in red in 1889.

One reactionary response to internationalism in Europe was ethnic nationalism. Unlike nationalism inspired by the French revolutionary model (which Benedict Anderson argues emerged first in Latin America), ethnicity, language and land were deemed defining features of the nation. There was no place for pan-European minorities like the Jews or the Roma. Ethnic nationalism saw a recrudesence of the most filthy mediaeval antisemitism, characterised by the Dreyfus affair in France and state-orchestrated pogroms in Tsarist Russia, and in the inter-war years, modern fascism.

Antisemitism is an inescapable part of the DNA of nationalism. Some on the left have argued that antisemitism is no longer significant, as all legal barriers to Jewish participation in public life have been removed. This is too mechanistic. Antisemitism will continue to be the ‘socialism of fools’ for as long as capitalism exists.

The prehistory of antisemitism

Ruling classes surmount the discontent that privilege and exploitation generates among subordinates through physical coercion and ideology. The latter directs the frustrations people feel with existing social arrangements towards false and innocent targets. The technique is an old one. It is, as the Romans put it, divide et impera, divide and rule. (Gluckstein and Stone, p.18)

Capitalism is not an abstract category. It has a specific history. It is ‘white’, European, for the most part. It suckled as an infant on the blood of African slaves. It sprang from a society where Jews, the ‘Christ-killers’, were a pan-European minority, despised but depended upon.

The mediaeval European economy was centred on agricultural production and had two major classes, landowners and peasants. Jews were excluded from agriculture and forced to congregate in towns and cities where they performed low-status work using skills acquired in the more advanced cultures of the Middle East, particularly in artisan manufacture and commerce (p. 33). The association of Jews with a special economic position, a ‘people-class’, made Jews a perfect safety valve for discontent.

This was reinforced by separate administration.

To perform its economic function the community was allowed to operate as a semi-independent island supervised by an institution called the Kehillah (community). Though tasked with keeping Jews orderly and segregated, it provided a degree of security and autonomy, education and community services, and maintained social cohesion. (Gluckstein and Stone, p. 35)

As Bundist leader Vladimir Medem put it: ‘The Jewish world was locked into itself; closed with two locks: one with which it locked itself off from the outside, strange world and another with which this strange world in turn locked it into a ghetto.’

Jewish responses

The Enlightenment (and its Jewish counterpart, the Haskalah) promised to end this isolation, especially its anti-aristocratic wing, which opposed aristocratic rule in principle: ‘Civil rights for Jews was one of its battering rams.’ (p. 24). Capitalist urbanisation concentrated the masses in centres of power so that politics was no longer the preserve of the privileged. When the alternative prospect of free self-expression was opened up by the French Revolution, the majority of Jews ran towards it (p. 38).

As capitalists supplanted the old aristocracy and consolidated their hold over society, they became less enamoured of universalist ideals. By the late 1800s, universalist nationalism on the French revolutionary model gave way to ethnic nationalism, the reactionary response to working class internationalism. For Theodor Herzl and other middle-class Jews, the Dreyfus affair showed the French republican ideal of universal citizenship to be a lie. The first World Zionist Congress, held in Basel in 1897, aimed to solve France’s Jewish Problem by enlisting Jews as colonial shock troops for a European empire, any empire.

By contrast, among the Jewish working classes, socialist politics became popular, especially in the east (the Jewish Labour Bund was one of the largest political parties in Tsarist Russia at the turn of the century). Central to the Bund’s politics was a celebration of Yiddish culture and ‘doykeit’ or hereness: ‘Instead of Zionist fantasies of reunification in the faraway vacant land of Palestine, the Bund grappled with the immediate reality of Jewish workers’ lives in situ.’ (p. 64) This vision perished in the horrors of Hitler’s extermination camps. There has never been such a wholescale, industrialised slaughter of an entire people. The 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising remains one of the most heroic events of our history but it was doomed. In the aftermath of this apocalypse, tens of thousands of displaced refugees, denied easy access to Britain or the USA, fled to Palestine.

Zionism in Palestine

Palestine has always had a Jewish population living alongside Muslims and Christians, but until the twentieth century it was a tiny minority. Zionism sought to portray it as a land without a people but the falsity of that was clear to anyone who went there. As Ahad Ha’am wrote in 1891: ‘From abroad we are accustomed to believe that Eretz Israel [the Holy Land] is presently almost desolate, an uncultivated wilderness ... But in truth it is not so. In the entire land, it is hard to find tillable land that is not already tilled. From abroad we are accustomed to believing that the Arabs are all desert savages ... But this is a big mistake. (p. 294)

With no imperialist army to grab land and distribute it for free, land had to be acquired piecemeal through purchase and settlers had to be attracted to work it. The USA, not Palestine, was the destination of choice for Jews seeking refuge from European antisemitism; between 1880 and 1924, 2.5 million moved there. Only after the US and other countries restricted immigration did significant numbers go to Palestine. Nor were these immigrants an ideal workforce. In a primarily agricultural economy, very few had farming skills and, worse, had subversive attitudes to bosses. As many as half of the migrants between 1919 and 1923 were socialists or communists!

David Ben Gurion, later the first prime minister of Israel, was himself once a Polish migrant labourer. He wrote that: ‘The Jewish workers had to stand by the synagogue until the Jewish farmers came to look for a labourer; they’d feel the worker’s muscles and take them for work or, mostly, leave them standing there.’ (p. 296)

‘Conquest of labour’

Employers preferred Arab farmhands, who were already skilled and, as smallholders, were cheaper to hire as they did not depend entirely on wages, whereas Jews were unskilled and needed work year-round. Ben Gurion’s solution was to force Arab workers out of the economy in order to ‘transform here the Jewish masses into workers.’ This was misleadingly called ‘the conquest of labour’. Gluckstein and Stone write:

‘Conquest of labour’ was presented as radical because the fight seemed to be with the landowners resisting the right to work. The slogan was the opposite of progressive, nonetheless. In class terms the sectional interest of one group was being placed over wider working-class interests, Arab and Jew together, and ethnic enmities were being fostered. (p. 298).

Israeli Labour Party politician David Hacohen (1898-1984) described the difficulties he faced convincing left-wing Jews of this colonial socialism:

I had to fight my friends on the issue of Jewish socialism, to defend the fact that I would not accept Arabs in my trade union, the Histadrut; to defend preaching to housewives that they not buy at Arab stores; to defend the fact that we stood guard at orchards to prevent Arab workers from getting jobs there.… To pour kerosene on Arab tomatoes, to attack Jewish housewives in the markets and smash the Arab eggs they had bought; to praise to the skies the Kereen Kayemet [Jewish Fund] that sent Hankin to Beirut to buy land from absentee effendi [landlords] and to throw the fellahin [Arab peasants] off the land–to buy dozens of dunams from an Arab is permitted, but to sell, god forbid, one Jewish dunam to an Arab is prohibited; to take Rothschild, the incarnation of capitalism, as a socialist and to name him the ‘benefactor’–to do all that was not easy. (International Socialist Review 24; 2002)

Apartheid communes, apartheid towns

The kibbutz (agricultural commune) movement, though small (only 8% of Palestinian Jews in 1948), served as a flagship for left Zionism as a whole. It inspired volunteers from urban environments to undertake the hardships of agricultural labour and disguised in communist colours the kibbutzniks’ dependence on Jewish capitalists to buy the land previously worked by Palestinian peasants. These communes ‘skilfully blended four factors—an image of radical communism, retention of immigrants, Jewish exclusivity, and colonial land settlement.’ (p. 300)

This pattern was replicated across the embryonic colony. Jewish exclusivity was a founding principle of Tel Aviv, where by 1939 one in three Jews lived (52% lived in Jewish-only towns). Zionists were deliberately building ghettoes while working class Jews in the Diaspora (which was 97% of Jews worldwide at the time) were fleeing the ghetto and enthusiastically embracing working class life and politics in every country they found themselves in.This deliberate insularity was also evident in the campaign to revive Hebrew: ‘This made Jews as well as Arabs the problem because at the time just one in 400 overall routinely employed Hebrew. By comparison, 1,000-year-old Yiddish was still the mother tongue for two-thirds of Jews in Palestine and 10 million out of 16 million Jews worldwide.’ (p. 301).

‘A strange trade union indeed’

If the kibbutz was the flagship of left Zionism, then the Histadrut (the General Federation of Labour) was its heavy infantry. From 1931 onwards, it counted 75% of the Jewish workforce as members, and ran banks, insurance and the largest shipping company: ‘...at one point, most of the Histadrut’s members were employed by subsidiaries of the Histadrut itself. “A strange trade union” indeed.’ (p. 303).

Behind the scenes, the entire loss-making Labour Zionist edifice was underwritten by non-socialist Zionists who ‘stomached the insults and flowery rhetoric about proletarian mission and the rule of labour because they knew colonisation could not succeed on a profit-or-loss basis ... an economically backward country like Palestine was unattractive to both capital and labour. Workers had to be enticed to stay.’ (p.304).

While some left Zionists from Hashomer Hatzair (later Mapam) were in favour of a bi-national state in theory, in practice they were heavily involved in ethnic cleansing in the Nakba and their support for kibbutzim, which provided the elite troops and officer class for the Israeli military.

Soviet support for the early state was also crucial. As Benjamin Balthaser put it in a Jacobin interview:

Ironically, perhaps, the Soviet Union did more than any other single force to change the minds of the Jewish Marxist left in the late 1940s about Israel. Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet Union’s ambassador to the United Nations, came out in 1947 and backed partition in the United Nations after declaring the Western world did nothing to stop the Holocaust, and suddenly there’s this about-face. All these Jewish left-wing publications that were denouncing Zionism, literally the next day, were embracing partition and the formation of the nation-state of Israel.

Zionist socialism was a militarised utopia. In egalitarian agricultural communes, the pathetic ‘Yid’ would be remade as a wholesome peasant and a super-masculine soldier.

The problem of Arab Jews

The downfall of left-wing Zionism was not only due to the contradiction between Jewish nationalism and socialism; racism towards Arabs, the horror inculcated in immigrants towards the indigenous culture, created a contradiction within the Jewish population as well: racism towards Arab Jews.

The early state faced a basic demographic deficit. In 1947, Jews were only a third of the population of Palestine. Although the majority of the world’s Jews lived in Europe, their destination of choice was the USA, not Palestine. Immigration from the Muslim world was essential. From the 1950s, hundreds of thousands of Jews were expelled from Arab countries as a result of a twin process of Israeli provocations and reactionary Arab nationalism.

The destruction of the millennia-old Iraqi Jewish community is a case in point. Iraq’s first minister of finance, in 1932, was Jewish, and in 1947 the Jewish population of Iraq numbered 156,000, compared to 630,000 Jews in British-controlled Palestine (most of whom were recent migrants). At that time the Iraqi Foreign Minister Muhammad Fadhel al-Jamali warned the UN:

Partition imposed against the will of the majority of the people will jeopardize peace and harmony in the Middle East. Not only the uprising of the Arabs of Palestine is to be expected, but the masses in the Arab world cannot be restrained. The Arab-Jewish relationship in the Arab world will greatly deteriorate. There are more Jews in the Arab world outside of Palestine than there are in Palestine. In Iraq alone, we have about one hundred and fifty thousand Jews who share with Muslims and Christians all the advantages of political and economic rights. Harmony prevails among Muslims, Christians and Jews. But any injustice imposed upon the Arabs of Palestine will disturb the harmony among Jews and non-Jews in Iraq; it will breed inter-religious prejudice and hatred.

Despite these prophetic words, al-Jamali was unable or unwilling to stop either Zionist provocation (including, allegedly, a Mossad bombing campaign targeting Iraqi Jews) or the legalised looting of Jewish property by the state, which eventually drove an ancient community out of Iraq to serve as second-class citizens in Israel. The pattern was repeated from Morocco to Iran.

Colonising the Oriental soul

Disdain for Arab Jews, for the East, drew on a deep well of anxiety in the Zionist tradition. In the late 1800s Eastern European Jews were on the move, escaping pogroms and poverty for the West. Baron Edmond de Rothschild, an important funder of Palestinian colonisation, was alarmed ‘by the plight of the east European Jewish masses and favoured their resettlement—though preferably not in France, where an influx of poor Jews from the east might fan the flames of antisemitism and undermine the tenuous place which the Rothschilds, and later other assimilated Jews, had secured.’ (p. 52)

This attitude towards the ragged, religious, Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jew was easily transferred onto Arab Jews. As the founder of right-wing Zionism, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, put it:

We Jews have nothing in common with what is called the Orient, thank God. To the extent that our uneducated masses [Arab Jews] have ancient spiritual traditions and laws that call the Orient, they must be weaned away from them, and this is in fact what we are doing in every decent school, what life itself is doing with great success. We are going in Palestine, first for our national convenience, [second] to sweep out thoroughly all traces of the Oriental soul.

Ironically, Arab Jews ended up voting for the ideological heirs of Jabotinsky.

Life for Middle Eastern migrants was hard. Thousands of years of history was lost. The diversity and richness of their cultures—Moroccan, Egyptian, Iraqi—were invisible to the European Jews who controlled the jobs, the housing, the police and the bureaucracy. Instead, they were seen as lazy and primitive. Strange to think now, but most early Zionists were militant atheists: the religious traditions of Arab Jews were evidence of their backwardness.

Bureaucracy was brutal. immigrants were shaved and sprayed with DDT on arrival and housed in shanty towns. Children were removed from their parents en masse; thousands were lost, giving rise to a continuing belief that Mizrahi babies were sold or given over to wealthy, secular European Jews. Many migrants, having lost their property and finding no work in Israel, suffered a severe loss of living standards.

The Labour Party, the party that founded the state, ended up being the party of an elite that looked down not only on Palestinians, but on about half of the Israeli Jewish population.

The oppressed turn on the oppressed

Before 1948 there were no Mizrahi Jews. The category was created by the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics to lump together Jews from Arab countries. Then, from the 1980s, in reaction to the persistent evidence of discrimination against Mizrahi and protests from Mizrahi, the Statistics Bureau stopped publishing data on Mizrahi Jews. The policy was reversed in 2022, but the general picture seems to be stark and persistent disadvantage in jobs, housing, income, education and incarceration.

The revolutionary wave that swept the world in the late 1960s and early 70s had an impact on Arab Jews. In the early 1970s, inspired by the Black Panther Party in the USA, frustration among Arab Jewish youth led to the formation of an Israeli Black Panther Party that briefly enjoyed mass support but was quickly marginalised.

More typical of the Mizrahi political trajectory is David Levy, who, as a young migrant picking cotton for an Ashkenazi-owned kibbutz, organised a strike over drinking water before going on to become a union activist. He helped weaken the power of Mapai in the trade union movement before going on to rally the Mizrahi working class behind Menachem Begin and the right-wing Likud Party, ending three decades of left-wing rule in 1977.‘Polls showed enormous support for the Panthers, but people were not prepared to vote for them. The person who identified this was David Levy, who was until then almost unknown,’ explained Sami Shalom-Chetrit, a scholar of Mizrahi social movements, to Davar Magazine in 2021. ‘There is no David Levy without the Panthers, there is no Likud as a popular movement without the Panthers.’

Levy’s solution to Mizrahi housing shortages? Government incentives for a new Nakba, a new wave of colonisation: settlements in the West Bank.

The absorption of most Mizrahi Jews into the right wing of the Zionist project did nothing to improve working- class living standards. Instead, Likud and its successors deregulated the economy and dismantled the welfare state. All that Mizrahi Jews have got from Likud is a rebranding of hummus as Israeli. The Israeli Labour Party is completely unable to challenge this—it won only 3.7% of the vote in 2022.

Conclusion: Ideology matters

Palestinians and their supporters may question the value of such a detailed account of Zionist politics. It is worth remembering the heroic role played by some left Zionists, such as Mordechai Anielewicz, in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, but by and large Zionism is a history of the oppressed turning on the oppressed.

Zionism is the story of the disdain of Western European Jews for Eastern European ‘Yids’, discrimination by European Jews in Israel against Arab Jews (and worse, Ethiopian Jews), and apartheid and genocide against Palestinians. It is the opposite of the radical Jewish tradition which, from Russia to the USA, was at the forefront of the fight against all manner of oppression and exploitation.

However, the erasure of this radical tradition was not easy and is incomplete. More, this account explains how a left-wing mask was essential to the establishment of Israel, to integrate immigrants and provide protective colouring internationally. The rise of far-right politics in Israel cannot serve the same purpose—rather the opposite. It is likely to lead to accelerating disintegration in Israeli society and to the alienation of international opinion. It is beyond the scope of this essay to examine the contradictory role of religion in Israel—a secular state guaranteed by God! Suffice to say it is not a stabilising force.

Ideology matters because the ruling class cannot do anything by itself. Capital uses other classes—including the working class—as instruments; political labels are how masses are manipulated. The creation of Israel as a militarised garrison state in the Middle East is a huge danger to the world. Understanding the evolution of ideology inside that state is essential to be able to see possibilities for ending the genocide and defusing the death trap. The absorption of Arab Jews into the right wing of Zionist politics is a warning to those liberals who naively look to Israeli civil society to end apartheid—only the Arab working class of the region and the Palestinians can do that. It is also a reminder that Zionism is unstable. As it lurches to the right it accumulates contradictions, which we can hope will open new possibilities for Palestinian liberation and, internationally, for a revival of the radical Jewish tradition.

Summary

Q. Why was support for left-wing parties so high in Israel in 1949?

A. Israeli electoral politics were unusually left-wing because although Zionism was a colonial project made possible by British and US power, the founding population was disproportionately drawn from refugees from Eastern Europe who brought left-wing politics with them. Zionist politicians used socialist rhetoric to recruit these radical immigrants to their colonial project.

Q. If the ‘left’ so thoroughly dominated the state and all its institutions, how was it so comprehensively supplanted by the right, without any constitutional rupture?

The apparently left-wing politics of the early state concealed an ethno-nationalist, colonial kernel. The ‘socialist’ veneer, so necessary to integrate left-wing immigrants and win international support, has been exposed by seven decades of colonial war—and the importation and subordination of Arab Jews by European Jews. Unlike in most countries, the Palestinian people, not the Israeli working class, have always been the main enemy of the ‘deep state’, whether controlled by the left or the right. The socialist rhetoric used to enlist European Jews to colonisation was exposed as a fraud by the subordination of Arab Jews, who revenged themselves by electing right-wing Zionists—the oppressed turning on the oppressed.

Q. What are the implications for Palestinian liberation?

A. The triumph of open ethno-nationalism and religious fascism has unleashed hell on the civilians of Gaza, but it has also damaged Israel’s standing internationally and is bringing tensions between secular, national religious and Orthodox Israelis to a crisis point. The shift to the right in Israeli ideology makes the state more volatile and more unstable. The Zionist project is running out of road—this is a moment of supreme danger.

Q. Why is a crisis in Zionism so dangerous?

A. Severe crisis in Israel is immensely dangerous for three reasons: its military capability; its importance to US hegemony internationally; the continued danger of antisemitism to the working class internationally.

Q. Why is antisemitism a danger to the working class?

A. Racism and ethno-nationalism are the most potent threats to working class solidarity. Like their extreme, fascism, they claim we have more in common with a billionaire of our ‘race’ than, say, the Filipina or Indian we work alongside. In times of crisis it can become frenzied. In inter-war Germany, fascists explained defeat in World War 1 as the work of a fifth column, hidden inside all layers of German society, that aimed to undermine the master race. That fifth column, they claimed, was the Jews, who had inveigled themselves into every country and every class with the aim of undermining the purity (and therefore strength) of the master race by encouraging inter-breeding with other, lesser, races—while jealously maintaining their own racial purity. While any ethnic minorities can be used as scapegoats—the fate of the Chinese in Indonesia is a grim example—the continued international dominance of a European elite means antisemitism is likely to be central to resurgent fascism in core capitalist economies.

[1] All references in the text are from this book, unless otherwise stated. There is also an edition published by Bookmarks in the UK.

Absent from the book was any mention of the fact that younger Jews (and a few of us oldies) are finding ourselves increasingly attracted to the heritage left by the Bund, with its notion of 'doikayt', hereness, as opposed to the ‘dortikayt' of zionism. This complements Walter Benjamin's term Jetztzeit, or ‘the time of the now’. Anyone interested might like to check out this Substack post:

https://tuwhiri.substack.com/p/doikayt-is-not-a-word-in-pali

One can generalize that the most oppressed sections of the working class globally have taken their revenge on the left (that is, the "social democratic" parties supported by the more affluent sections of the working class including the lower ranks of the professional managerial class, state servants and so on) by helping to elect the right to power. So this is not a uniquely Israeli or Zionist phenomenon.

The problem here is not anti-Semitism as such. More widely, it is Jewish exceptionalism. That is, the view held both by Zionists and anti-Jewish fascists, that the Jewish people are in some way exceptional, neither bound nor protected by the rules that normally govern the conduct of civilized peoples.