The Alliance - a political tragedy (part 2 of 2).

Victor Billot wraps up his reminiscences and considerations on the Alliance Party and its fate. First published in The Commonweal volume five in May 2024.

The previous instalment of my personal history of the Alliance in the October 2023 edition of The Commonweal discussed the ‘first three acts’ of the political tragedy that is the Alliance Party.

The first act saw the dramatic events of the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the Labour Party split and the NewLabour Party (NLP), under the leadership of Jim Anderton, emerged as the torch bearer of the left. The second act was the formation of the multi-party Alliance (including the NLP and the Greens) and its challenge to the Labour/National duopoly.The third was the entry of the Alliance into Parliament in substantial numbers in the post-MMP 1996 election, the coalition Government the Alliance formed as a junior partner to Labour in 1999, and its subsequent catastrophic failure to survive even one term in Government. The ‘fourth act’ which I will discuss now is ‘life after Parliament.’

During the years following the 2002 election the damaged remnants of the Alliance attempted unsuccessfully to rebuild. Despite the best (even heroic) efforts of many, the party instead gradually faded into oblivion. This process took a while. I devoted over a decade of my life to trying to keep the dream alive. Looking back it was perhaps a fool’s mission, driven by a refusal to face facts. My view was that keeping a flame alive would one day reignite and bring the vibrant movement I had known back to life. There’s a song ‘It Was’ by the legendary Dunedin band The Verlaines on their classic album Some Disenchanted Evening. It has an evocative line—‘he mistook the dawn for the sun as it was going down.’ A bit close to the bone perhaps.

Many of those who abandoned the Alliance (or who tried to scuttle it on their way out) said those of us who stuck around were misguided bitter-enders at best. There may be an element of truth to this. However, despite the failure of the Alliance, those who abandoned it also failed to build a viable political vehicle, or simply threw their lot in with the established parties. What follows is an impressionistic account. A proper history of the Alliance would be a worthy project, but this is not it. I’m still too emotionally attached to it all to be even vaguely objective.

Life in the Capital

The 2000–2001 period was where the Alliance had started to go seriously off track. The party had become professionalised. There were paid staff and machinations going on behind the scenes at Parliament, garbled accounts of which filtered down to the minions like me in the ‘outer party’. It seemed the closer the Alliance got to power, the more it slipped away from what it was about. On the way up the Alliance had been authentic if nothing else. But now it was failing on the one hand to be a radical movement holding Labour to account, or on the other the successful political machine of the domineering but effective Jim Anderton. Jim and others often talked about the ‘realism’ necessary for effective politics. The cliche was to ‘build your paths where the people walk.’ Of course, if Jim had followed his own harsh pragmatism and treated getting/holding power as the be all and end all of politics, he would have never stood up to the Rogernomes in the Fourth Labour Government and walked away to start a new party.

This period has been covered in a number of other memoirs and biographies of the main players, so I won’t expand on it here. I wasn’t a main player—I wasn’t even a minor player. My view is a worm’s eye one. In 2001, when all this went down, I was living in Wellington and attending the meetings of the small Johnsonville branch.

I used to drive up from town in my Toyota with three young women about my age (one of whom, Rebecca Matthews, is a Labour councillor for the Wellington City Council these days). We were all dedicated and active members. The Johnsonville branch was held at the home of a retired working class couple. There were usually a few others there, including a public servant in the health system and a convivial elderly Irish guy Patrick, who described himself as anarchist. This was not inaccurate. Patrick and the healthcare guy had a long running feud about tobacco policy—Patrick was a smoker and claimed banning cigarettes would take away the last small pleasure from the oppressed workers. This was a classic example of the middle class, rational, and socially improving outlook versus the old school world of pints and ciggies. Debates would rage. It was democracy in action—inefficient, a little eccentric, often funny. I miss it.

In 2002 I stepped back and (briefly) resigned my membership as I was at journalism school and was interning at Newstalk ZB at the press gallery. I had a vague idea this might be a career option. The experience was a good one in that it convinced me Parliament is basically a negative place which has little to do with democracy. I was working in a tiny, cluttered office. Barry Soper (yes, him) was in charge, and he had been there forever, even twenty years ago. Say what you like about Barry, he took pity on a hopeless case. I had turned up to work in smart casual which was not going to cut the Parliamentary dress code. Barry donated to me his spare formal wear which was hanging in a tiny cupboard which doubled as a recording studio. It was a monumentally hideous 1980s olive green zoot suit with enormous lapels. It made me look like a cross between a member of Split Enz and a budget rate mafia informer.

I wandered around Parliament feeling like an inmate in a giant asylum. In the next seat of the tiny office was Corin Dann, who was obviously going places even at that point, busily tapping at his screen. I met a few other denizens—including the former TV newsreader turned libertarian advocate Lindsay Perigo, whose persona as a writer was aggressive and acidic. Off the page he seemed friendly and low key.

One day I had the opportunity to stop Steve Maharey on his way into a cabinet meeting with a question. He grinned and gave me my big break with a quick response into my microphone. The other press gallery hacks looked on at my presumptuous standup interview with the Minister. When we were walking back to the office Barry congratulated me. ‘That was good how you asked that question’, he said, ‘but you asked the wrong question.’ He gave me a nice reference when I left.

On my first day I had walked up the path to the Beehive with a sense of manifest destiny. Finally, after frittering away my twenties, I had ‘arrived’. By the end of my internship I realised that this was not a place I had any connection with. It felt like the opposite of the hall meetings and doorstep conversations, the protests and pickets, the lounges and flats and pubs where discussions were thrashed out. It felt, despite the grand corridors and aura of power, like a bit of a shithole. Despite all this, I maintained (and still maintain) my belief that a serious socialist party has to seek representation at all levels of the existing imperfect democratic structures, while remaining critical of their limitations.

Around this time, I had also found work with the Waterfront Workers Union as a campaign organiser in Port Chalmers at the tail end of a nasty industrial dispute. Although I arrived a bit late to be of much use, this proved to be a life-changing decision. The wharfies were in the process of amalgamating with the Seafarers Union, and after my role ended I talked my way into a permanent job—and with a break of a few years have ended up spending the last two decades working for the Maritime Union. Ironically, I think I have had far more impact on politics with union work than through actual political parties, but that is a story for another day.

Exit stage left

On election night 2002, I’d headed up with my friends to an election night party up the back of Aro Valley. A mobile call came through to someone in the car from Gerard Hehir, a longstanding Alliance organiser. The numbers in Laila Harre’s electorate of Waitakere were not looking good. It was apparent the Alliance was not going to make it back into Parliament.

Laila had been our one chance—she was popular, youthful and charismatic, the natural choice for a new leader. But the damage done by the split had been too great. The Alliance fell far short of the 5% threshold to get list candidates elected (closer to 1%). The last roll of the dice of getting Laila across the line in an electorate had failed. The Alliance was out of Parliament. It was a strange night and depressing, obviously. I was in a fatalistic mood and one of my old comrades got upset with my resigned attitude. The collapse of the Alliance was overshadowed naturally by the resounding return of the Helen Clark Labour Government, and the drubbing of the Bill English led National opposition. The Greens made it back in, as well as Jim Anderton and one of his loyal sidekicks.

Jim had won the battle and lost the war (I suppose you could argue that the Alliance had lost the battle and the war). He had quelled the rebellion of the left in the Alliance and seen us off. But his purpose now was unclear apart from making up the numbers for Helen Clark. He spent his remaining time in Parliament as a kind of pointless satellite to Labour. He had come home in a sense. I always felt his decision had been a psychological one as much as a political one.

For me, the idea of the Labour Party being a ‘home’ was impossible. I had spent over a decade witnessing their perfidy at first hand, all the bullshitting, and the legacy of Rogernomics which the Labour Party still to this day places a cone of silence over.

He mistook the dawn for the sun going down

Not long after the election defeat, there was a national conference in Wellington at the Tinakori Bridge Club. This was not on the scale of the old time Alliance conferences, which were attended by hundreds in giant venues. However, there was still a good chunk of seasoned activists, ex-MPs, and members. The people with initiative and campaigning skills had largely stuck with the Alliance. Jim tended to attract people more comfortable with being told what to do. I went away thinking there was a future, and a road back. There were a lot of younger members still involved. The youth branch had the cringey name of Staunch Alliance, but it in fact lived up to its macho name and staunchly stuck with the Alliance.

In 2003 I moved back to my hometown of Dunedin for good. We had a solid and active branch, smaller but still viable. Regular attendees included academics, some retired people, union types, and a few colourful and occasionally frustrating characters. All the decent union organiszers and delegates in Dunedin seemed to be in the Alliance at this point. They only drifted off later on. Part of the problem here perhaps was the Alliance had never had a particularly strong ideology of what it was about, which meant that when the chips were down, people didn’t have a clear analysis or plan to fall back on, and just reacted emotionally. On the national scene, things were starting to unravel. The movers and shakers seemed to be looking for short cuts back to power.

Laila had remained as co-leader, but it seemed her heart was not in it. Matt McCarten had become the other co-leader after years of remarkable successes as Alliance President. However, along with his UNITE Union activities, he and other key party activists in Auckland were engaging with the new Māori Party, at that stage led by ex-Labour Party Minister, Tariana Turia. The Māori Party had grown out of the movement against the Foreshore and Seabed legislation, one of Helen Clark’s rare missteps.

There was a strong push for the Alliance to get in behind this growing new party. It was always unclear whether the strategy was to merge into them or leverage them as an ally to help us get back in the game. I was dubious about how the process was playing out. Once again, it seemed like the people ‘on the inside’ were busy making the calls and sidelining the actual membership. I was dubious about becoming a clip-on to a party based around ethnic identity. There was no intrinsic left-wing component. I thought there might well be a place for a Māori Party but I didn’t want to be part of it. The signs were there that Tariana was about cutting deals with whoever would ‘deliver’ for Māori. Even if the support was largely coming from marginalised people, it didn’t follow that policies would align with socialist values.

Things seemed to rapidly go downhill. There was a personalised and ugly fight going on via email groups. Factions formed, and more and more people just started to walk away. I was told by a newly arrived German guy called Norbert, who had been an Alliance member for a relatively brief time, that I was racist and didn’t understand Māori issues. Naturally I offered my own thoughts back in an equally frank manner. It was not a positive environment. Clear communication and democratic processes were not in evidence. There were arguments and accusations about missing sound gear, about financial support to the Māori Party. By the end of 2004 the key leadership walked.

Matt McCarten told the media after his resignation that the Alliance was finished. Jim had said much the same thing. Once again the bottom had been smashed out of the Alliance boat by those who had spent years building it up. It seemed people in leadership positions had a sense of ownership of the Alliance, and when they didn’t get their way, they would make sure they did some damage before leaving via the exit.

My process of disillusionment was fairly advanced by now. I had seen several waves of people I had regarded with respect and even awe turn on their own supporters, the people who had backed them and lifted them up. I’m sure people on the other side have a different story. But I was shocked at how the talk of ‘unity’ and ‘solidarity’ so beloved of the socialist left was thrown out the window, and how sharp dealing seemed to be the way things were done. Perhaps it was a lesson I needed to learn. It certainly made me suspicious of the hierarchies that seemed to establish themselves in organisations supposedly dedicated to equality.

The Alliance had basically lost its entire Auckland base. There were still functional branches in Christchurch and Dunedin. Two union organiszers were elected as co-leaders—Jill Ovens (from the Service and Food Workers Union, now part of E Tū) and Paul Piesse, from the SLGOU. Later on, Kay Murray in Dunedin and Andrew McKenzie in Christchurch filled the co-leadership positions, and I even had a brief turn myself.

On the campaign trail

The Alliance stood in the 2005, 2008 and 2011 elections, with a limited number of electorate candidates but a full party list. During that time, our share of the party vote was minute and never grew.

The Alliance had gone into the 2005 election in battered shape. The two South Island branches in Christchurch and Dunedin were still functional with some solid and talented activists. Elsewhere the numbers were too small. Ideologically, the party was now more coherent (I am struggling to find positives here.) It basically comprised the remaining left wingers of the NewLabour Party from fifteen years earlier. People like Len Richards and Bob van Ruyssevelt in Auckland, Professor Jim Flynn in Dunedin, and a good crew of Christchurch activists (several of whom are now CSS comrades). Julie Fairey, now a Labour city councillor in Auckland, was on the party list. I stood in Dunedin North, my first experience, and polled a modest 270 candidate votes. Our overall list vote was so small as to be off the charts. It was worse than I had expected.

However, the campaign had been something of a revelation. I realised I was not too bad at campaigning. I had picked up some public speaking skills, and knew how to talk into a microphone from my years playing in punk rock bands. It’s amazing how this one very basic skill is something that a lot of rookie candidates simply don’t have the first idea of. I gained a reputation for being the loudest speaker on the meeting circuit and adopted an old school soapbox persona. I was probably quite annoying, however my goal was simple—to get noticed, and to insert some socialist policies into the election campaign, even if on a small scale. My media background helped, and I started making regular appearances on the local TV and radio.

Moreover, I was motivated. I was angry at the state of New Zealand and what I saw as a compromised Labour Government, that had held on to the core of the neo-liberal policies of National we had fought so hard against. I was also angry at the mainstream union leadership that had cravenly fallen into line behind the same ideas, even though I was forced to get along with them. The Maritime Union was a curious situation for me—it was technically affiliated to the Labour Party, yet it seemed more like a difficult marriage than a love match. MUNZ tolerated socialist dissent in its ranks and appreciated robust debate, unlike some other Unions where being critical of Labour basically made you persona non grata.

FIRST (as the NDU evolved into) and UNITE remained outside the Labour tent. The public sector unions were officially politically neutral, but their leadership tended to be centrists in lock step with the Labour establishment.

My first campaign did gain a high profile locally—I was either up against Labour candidates who were planning to sleepwalk to victory, or token National candidates who might as well have been cardboard cutouts. They didn’t seem particularly political, in fact seemed to prefer avoiding talking about politics. There were professional politicians, MPs who were efficient and business like, and who obviously had little interest in politics as a tool for social change. Elections were obviously an inconvenience. Pete Hodgson, the local Labour MP, was slightly more of a character. He would get frustrated with dumb questions at public meetings, and snarl at audience members. He made little or no effort to come across as a jovial man of the people, yet election after election he would be returned with a large majority. In the 1990s Jim Flynn had come close to knocking him off his perch. Hodgson was equally exasperated and amused by my class struggle invective. He told me I was like some cloth cap unionist out of the 1970s. It was not a compliment, but I took it as one.

The second group were the conviction candidates—everyday people who had come out of the woodwork to express their principles and stand on their beliefs, often for minor parties. Many had a whiff of eccentricity. The religious ones were worst. The local Destiny candidate was thick as a plank and tried to threaten me for making fun of Brian Tamaki. I just grinned at him. Another was a fundamentalist Catholic who had his own one-man political party. He used to send me lengthy hand written letters, disproving my atheism through the arguments of St Thomas Aquinas. I ended up quite enjoying his company at campaign meetings, as his views were essentially mediaeval and used to outrage the liberals. He was obviously very intelligent, but completely mad.

Other candidates were paper candidates for minor parties, just carrying the flag. There was one candidate for United Future who hated public speaking, yet turned up to all meetings to give a painful and fumbling presentation. One night at the Coronation Hall Meet the Candidates event, after we agreed on some random point during the speeches, I made a joke that we could go into coalition together. The audience laughed, but I saw a flash of horror in his eyes that perhaps I was serious, and he had somehow entangled his party with a communist in Dunedin.

Actually, I had great respect for people who were well out of their comfort zone yet turned up to do their best. I find speaking easy—I enjoy it—and large audiences do not faze me. But we all have something we are afraid of. I am terrified of heights. So I appreciate the feeling of dread that must come over those who are terrified of public speaking.

After the 2005 experience the Alliance had a brief period with no leaders, to focus on getting back in the game. In 2006 there was a very small conference in Wellington (I remember Don Franks came along and played some songs on his guitar for us.) I was elected as Party President with a plan to try and reboot the party and I took my job quite seriously. The Alliance received a little media coverage, largely from me working my contacts, and occasionally appeared at the bottom end of opinion polls. One issue we got some national coverage for was when I criticised Air New Zealand for paying their Chinese resident cabin crew less than their New Zealand ones. But generally it was an uphill battle.

The membership hovered around the 500 mark but most were paper members. Maybe 10% were active. I managed to sign up quite a few maritime unionists, but they were really doing it mainly as a favour for me, or to get me to leave them alone. I addressed Maritime Union stopwork meetings in Auckland, Wellington, and Port Chalmers, and received branch donations of several thousand dollars. I thought this was good going, given the Union was a Labour Party affiliate. No doubt the Labour Party people would have screamed in horror if they had found out about it.

In the end, despite all the work, the 2008 election was a repeat performance of 2005. Nationally the vote was about the same. I increased my vote as an electorate candidate in Dunedin North in 2008 to 448 votes, which was still hardly impressive, although better than any other Alliance candidates.

Drinking at the Last Chance Saloon

The one last chance we had of getting back to Parliament was an interesting story.

Prior to the 2011 election, a former MP reappeared on the scene. Kevin Campbell had served as an Alliance list MP from 1999–2002 in the coalition Government. He was a former policeman of all things, and had become a community lawyer in Christchurch. He was very much in the Anderton mode in his personal beliefs, a practicing Catholic of the ‘social justice’ mode. I remember him once asking at a conference for people to stop calling each other comrade as it would alienate people (he was probably right.) He was close to Jim but had walked away after the Alliance collapse in 2002.

We had a distant family connection, and I had actually met him through this. He was itching to have another crack at Parliament. I liked Kevin a lot as a person—he was a genuinely nice guy, probably too nice for politics, as he always saw the best in people. But we did not share identical political ideologies. He was a social conservative on moral issues, and a principled social democrat on economic issues. He genuinely believed the Alliance was necessary to create a more humane society.

One area where I disagreed with Kevin was his belief that the Labour Party could be convinced they needed a junior coalition partner, and that the Alliance could play that role again. Fat chance! The Labour Party is far less pragmatic than National, who kept ACT on life support for years. Labour have a ferocious patch protection mentality, that is strangely out of sync with their weak and co-opted political positions. Besides which, they already had the Greens.

Kevin ran in Wigram in 2011 and got 793 electorate votes, far behind the Labour candidate Megan Woods (an Anderton protégé) and her National competitor. Once again, a bit like me in Dunedin, Kevin had collected personal votes rather than party votes. In a sense, that was the last test. Could a credible figure like Kevin, a well-known and popular local identity with wide networks and previous experience in Government, lead a left- wing voice back into Parliament? The answer was no.

After three elections outside Parliament the Alliance was very much a spent force. After ten years of heavy and constant involvement, and over twenty years of membership, I drifted away. I was washed up. The Alliance formally deregistered as a political party with the Electoral Commission at its own request on 26 May 2015. There was some confusion that this meant the Alliance was gone. But the deregistration was required because the party no longer had 500 financial members. It meant the Alliance was ineligible for running a party list, but there is nothing stopping a non-registered party from having electorate candidates in elections. The party was never dissolved and continued on for a few years in a kind of dormant mode. But my active involvement was over.

Where are they now?

A few of the most well-known figures from the Alliance experience have ended up at the heart of the political establishment, former Labour Government Minister Willie Jackson, for example, who stuck with the Alliance for a while after the split in 2002. He is one of the few modern day Labour people who actually came out of a working class milieu. Ironically, he came into the Alliance via Mana Motuhake, a kind of precursor to Te Pati Māori. He certainly has had an impact with his role in the Māori caucus and the co-Governance debate. Compare the massive shift in Māori politics in the last twenty years to the absolute silent wasteland of class politics in New Zealand.

Others have bounced around the unions and politics on curious trajectories. Laila Harre was one example, and so was Matt McCarten. Both very talented individuals who nonetheless seem to have failed to effect change (I’m not saying anyone else has—it may be that change is no longer possible by people doing ‘stuff’, and that it requires some massive outside cataclysm.) Matt ended up working for Labour Party leader David Cunliffe at one stage, which was quite mind boggling.

Another long time Alliance activist Jill Ovens ended up setting up the TERF-aligned Womens Rights Party at the 2023 election, after years with Labour (the WRP did even worse than the Alliance.)

Many of the general Alliance membership drifted back to Labour or went to the Greens. Many just vanished from politics. Of course, the generation who were middle aged when the Alliance started are now either retired or dead. Other names crop up now and then in various roles. A lot of us had positions in the unions, either as active members or organisers, despite the fact that the unions tend to be dominated by Labour Party mandarins. Robert Reid was President of FIRST Union for many years, which grew out of the NDU (which had Labour, Alliance and communist factions when I worked for them in the 1990s.) One time Dunedin Alliance activist Sam Huggard later served as Secretary of the Council of Trade Unions.

Others have made their way into academia, Māori politics, and some just ended up making peace with the system and became managers, businesspeople, and senior public servants. Former Alliance staffer Bryce Edwards is now a high-profile political analyst and academic in Wellington. Others returned to private lives and normal existence. Some became active in other forms—long-time Dunedin Alliance member Jen Olsen was recently charged after peaceful civil disobedience in environmental campaigns. And some have reappeared in the Socialist Society, including old comrades such as Quentin Findlay, Chris Ford, Paul Piesse, Denis O’Connor and more.

What’s left?

So, what was the impact of the Alliance? Was it a waste of time, a flawed but worthy venture, or a success?

I would argue the second point. Labour parties throughout the English-speaking world went through a transformational process over the last decades of the 20th century. The NewLabour Party and then the Alliance in New Zealand pursued a brief and spirited fight to maintain social-democratic policies against the global power of capital and its local lieutenants. The Alliance halted the rightward drift of New Zealand politics—of this I am sure. But a rightward drift had already occurred, and the Alliance never had the numbers to move New Zealand back onto a more leftward trajectory. We were locked into a particular future, which we now find ourselves living in.

MMP had a similar effect. By permitting smaller parties such as the Alliance and New Zealand First into the system, MMP ended the possibility of radical change occurring through elections in New Zealand, either back to the left or further to the right. But the horse had already bolted, so MMP had the perverse effect of locking in the anti-democratic capitalist shock therapy of the 1980s and 1990s.

‘Capitalist realism’ had become established and the damage had been done. National and Labour have both rolled back to a more centrist mode in the last twenty years. Labour has even made small concessions, but when push comes to shove (such as capital gains taxes) it makes it plain that ‘transformation’ is no more than a marketing buzz word.

On the other side, Sir John Key was a classic example of a leader of a status quo, managerial, in his own words ‘relaxed’ type of right wing Government. He made jokes about Kiwis being socialists at heart. All the heavy lifting had been done, and it was just a case of maintaining the steady extraction of surplus value from the working class for the rest of eternity.

But if the Alliance was ultimately a failure, those who derided or dumped the Alliance did not have the magic answers either. Jim Anderton’s post-Alliance vehicle was known as the ‘Progressive Coalition’ (it included the Democrats) and it then changed its name to the Progressive Party after the Democrats jumped ship. In 2005 it was embarrassingly renamed Jim Anderton’s Progressive Party, just in case anyone had any doubts about who was in charge. Jim hung around as a lone operator, a Labour MP in all but name, easily winning his Wigram electorate as a popular local MP until he retired in 2011. But the party vote slowly evaporated and the Progressives deregistered in 2012.

Despite the fact I grudgingly vote for them these days, the Greens are (evidently) a ‘green’ party. It’s an ideologically, culturally and historically distinct movement. In 2024 it has become even more a vehicle for identity politics and inner city hipsters.

The sad case of Golriz Gharaman, whose career ended after shoplifting high end frocks from a central Auckland boutique, seemed to be something of a grim metaphor. The last big Green scandal had seen Meteria Turei being overly honest about her past efforts to survive on a benefit.

The days of Rod Donald, Sue Bradford, Jeanette Fitzsimons and even Nandor Tanczos are long gone. I felt like they were political relatives—the new generation I don’t feel the same affinity to. That said, the Greens are the closest to what the Alliance was. I know plenty of Greens who I have a lot of time for—and of course we have a number of Greens in the Socialist Society. Still, I have never felt moved to join the Greens myself. Their recent performance makes me feel even less enthusiastic. They have become a repository for disillusioned left-liberal voters having a temporary ‘rage quit’ on the Labour Party. On the other side, a strong argument was made in the last Commonweal by Green candidate Francisco Hernandez for socialists to involve themselves with the Green Party rather than reinvent the wheel.

I suppose you could say the Greens are at least semi-functional, which is an achievement in itself on the left of New Zealand politics.

One of the weirdest developments of the last three decades was the Internet–Mana movement. After the big fight with the pro-Māori Party faction in the Alliance in 2004, the Māori Party under Tariana Turia’s leadership did end up throwing its lot in with National in Government in 2008—not that anyone admitted getting that particular strategy wrong. Tariana Turia herself is now long gone from Parliament but has made a number of bizarre claims in recent years.

Of course there is not enough room here to cover all the subsequent developments, but in brief the Māori Party split and the more radical faction became the Mana Party. Quite a few ex-Alliance people got involved as well as a lot of the revolutionary socialist groups. The idea was that Mana and its leader Hone Harawira were going to form the basis of a radical left movement. Hone was genuinely on the side of the marginalised and downtrodden but his politics were all over the place and he obviously had his own priorities. I was sceptical and believed Mana would never become a major player as it was a largely regional, obviously ethnic-based phenomenon. Hone Harawira was an acquired taste and would never cross over into appealing to most people. However, the few left wingers still around were largely absorbed into the Mana project, and this contributed to preventing any prospect of the Alliance rebuilding. We all know how it ended!

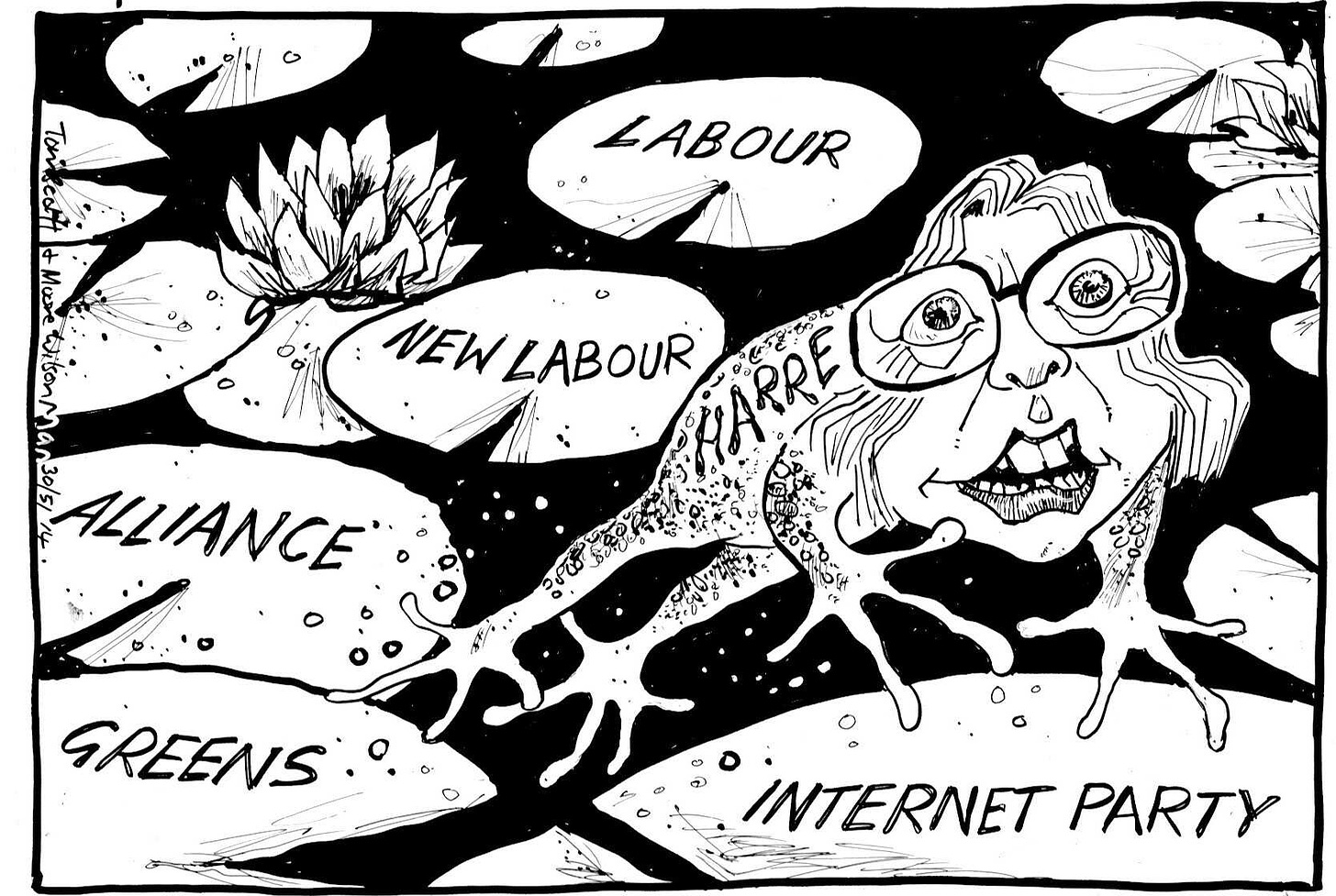

In 2014 the New Zealand domiciled German IT entrepreneur Kim Dot Com became a booster for an ‘Internet Party’, promoting a kind of high tech utopianism. Dot Com himself owned a mansion and a collection of high end sports cars, had made large donations to John Banks’s mayoral campaign, and in 2012 had been arrested in a massive raid by armed police on his home on behalf of the FBI who were pursuing him for racketeering, copyright infringement and conspiracy to commit money laundering. Things took a turn for the bizarre when in a carefully stage managed ‘big reveal’, Laila Harre was presented as the new leader of the Internet Party, looking like a Blakes Seven actor in some futuristic publicity shots.

An ‘alliance’ between the Internet Party and the Mana Party then contested the 2014 election on a joint party list. The campaign was a high profile disaster. Hone Harawira lost his seat, Laila Harre resigned as Internet Party leader, and Kim Dot Com resumed his attempts to avoid extradition to the USA for alleged international cybercrime. If the collapse of the Alliance had been history as tragedy, then the implosion of Internet–Mana was farce. It severely damaged the credibility of all involved. The question of why politically savvy leftists became embroiled in an adventure with a sketchy and large living fat cat like Dot Com still mystifies me to this day. It is a telling reflection on the degeneration of the political left.

Phoenix or dodo?

So much for the various attempts to reignite a radical left in 21st century New Zealand. It often occurs to me that the people who had been in the Alliance, once united under the banner of a common cause that posed a major challenge to the establishment, then spent the next twenty years divided, scattered, and making little difference, or actively harming the cause. I find the absence of a socialist party or even a serious, principled social-democratic party with a working class focus to be a stunning vacancy at the heart of New Zealand politics. Where are the socialists?

I am constantly reminded how I belong to a statistically insignificant minority. The New Zealand socialist today is a rare bird—endangered—perhaps as doomed as the dodo. The isolation and tiny scale of our small time movement creates an unhealthy environment. A few abrasive personalities litigating ancient grievances often create a poor impression for those looking for answers. Politics, like religion, can attract troubled people whose issues are personal as well as political.

The reality is, even in a left leaning city like Dunedin, I would guess my friendly tradie neighbours with their utes and Saturday barbies will vote National (the neighbours on the other side are old punk rockers so possibly more on my end of the spectrum.)

Most people in New Zealand passively go along with capitalism. They see politics through an emotional lens, with odd prejudices and little consistency. That is the ones who think about it at all. A large minority support the National Party. A good minority support ACT or NZ First (a few of the old school Alliance types I knew drifted towards Winston.)

A large group, mainly in the lower socio-economic groups, do not understand politics, have no interest, think it’s ‘all bullshit’ (understandable) and hate politicians. Others do not pay any attention; they are just not interested in something that appears to have no relevance. You might as well be talking about the business affairs of Martians. Some people have such pressing problems in their lives they don’t have the time or energy to pay attention. They are fatalistic or realistic, in that they correctly guess they are not important in the scheme of things.

These people—the vast majority—outnumber socialists a hundred to one at best. Probably more like a thousand to one. If we had one person out of every thousand New Zealanders join the Socialist Society, we’d have five thousand members. Probably a similar size to the Destiny Church.

Even so, the appearance of the Socialist Society has been something of a surprise to me. It evokes mixed feelings. Hope can have a bittersweet taste. I have found a political home for now and find myself impressed with the spirit of openness and respectful debate (and the organisation). I have even been reunited with past Alliance and revolutionary socialist people, some of whom I had disagreements with in the past. Time has given us new perspectives and perhaps the hard experiences have improved us in some ways.

I joined the NewLabour Party in May 1989—a founding member. Apart from a brief period I remained an NLP and then Alliance member since that time. I was part of a small group who were there at the dramatic beginning and the quiet, sad end.

The political is personal

Politics is about public life at heart. But every political experience is also a personal journey, and every personal journey is different. I sank countless hours of unpaid work into the Alliance, along with many others. This ranged from the dreary (printing forms, licking stamps) to the interesting (TV interviews, making election videos, designing and editing manifestos.) I debated, I argued in pubs, I sat in draughty halls, I went on inspiring marches, I sat on stalls and wrote letters to the editor (the sign of a true obsessive). I was fortunate in that I had a sympathetic employer for much of the time.

However, for all the effort, the thing that wore me down the most was the growing sense of being on the outside. Up to 1999, although I was merely an active grassroots member, it felt like change was possible—we were the underdog, but what a fight! After the 2002 catastrophe, it was a long decade of relentless disappointment and struggle. Without sounding too much of a hippy, it became exhausting and degrading on a spiritual level.

Personally, on top of life with a young family, it was too much. I eventually became clinically depressed, in a dim and dark place for several years. I was on medication and functioned but it was a bad situation. Other things were going on in my life, but the negative influence of politics added to the weight. I note I am not talking about the remaining few comrades in the Alliance at this time, most of whom were very good people, but just the relentless trajectory of doom.

It became hard not to be embittered and it was a long road back. The depression faded but it left its mark and I manage my life a lot more carefully these days.

I will never be able to return to the level of involvement I had. For one, I’m now middle aged, with teenagers in the house. I used to wonder why there were young people and old people at meetings, but very few middle- aged people. Now I know why—they have gone to bed. But more seriously, I still suffer from some low level political trauma. I can’t bear to watch debates on TV. On election night, I stay home and pay no attention, and read about the results in the morning. I find attending meetings stressful and unpleasant. I have no patience for the inevitable cranks, or the time wasted on trivial discussions, which are an intrinsic part of inclusive democracy, but also the flaw.

My political views have remained entirely consistent for my adult life—I still see myself as a democratic socialist, a ‘reformist in a hurry’, with a vaguely Marxist view of history. But my ability to take part in practical politics is limited.

I guess if there is any lesson to offer from this, it is my entirely non-original advice to young people—pace yourself, look after yourself, and keep your friends close. And be aware the people who get you running around to deliver leaflets one day, can quite easily be doing a hatchet job on you the next.